Your Worst Enemy Has a Brokerage Account

It’s you. It’s always been you. Or has it?

For decades, one study has told investors they’re sabotaging their own wealth. But what if the real sabotage is believing that story?

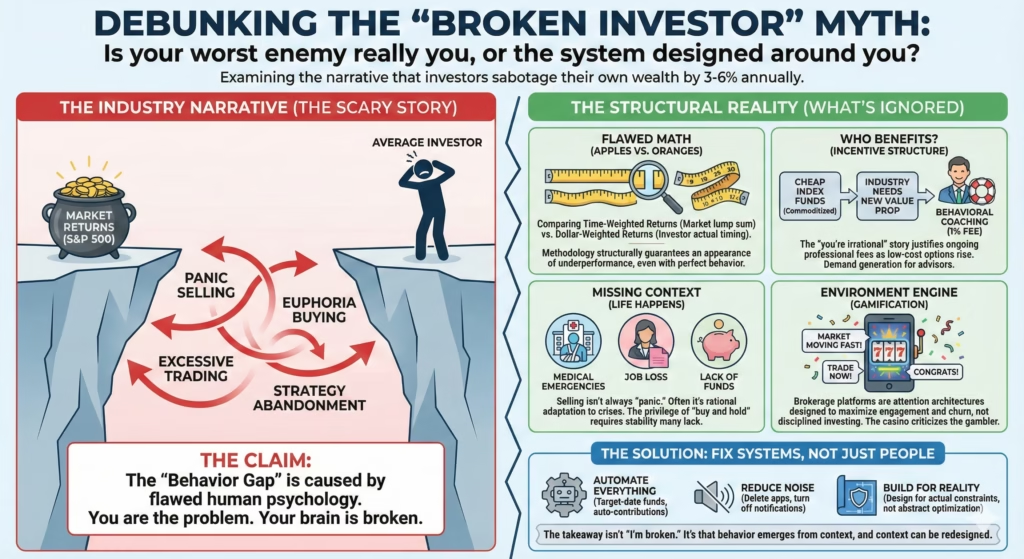

There’s a number that haunts the financial planning industry like a ghost that won’t stop rattling chains. It varies year to year, but the melody stays the same: somewhere between three and six percent. That’s the annual gap, we’re told, between what the market delivers and what investors actually capture. Over twenty years, compounded, that gap doesn’t just erode wealth—it vaporizes it.

The source is DALBAR, a Boston-based research firm that’s been publishing its Quantitative Analysis of Investor Behavior since 1994. The findings have become canonical, cited by financial advisors, passive investing evangelists, and behavioral economists with the reverence usually reserved for scripture. The message is simple and brutal: you are the problem. The market is fine. Your brain is broken.

It’s a compelling narrative. It’s also worth interrogating.

The Gospel According to DALBAR

Here’s how the story goes. DALBAR tracks fund flows—when money enters and exits mutual funds—and calculates what an average investor actually earned based on the timing of those flows. Then they compare that figure to the S&P 500’s return over the same period. The gap, year after year, is staggering.

According to DALBAR’s 2023 report, the average equity fund investor earned 6.81% annually over the preceding thirty years, while the S&P 500 returned 10.65%. That’s nearly four percentage points left on the table, every year, for three decades. The culprits, per DALBAR: panic selling during downturns, euphoric buying during rallies, excessive trading, and strategy abandonment before returns materialize.

The implications ripple outward. If the primary risk isn’t market volatility but human psychology, then the prescription writes itself: stay disciplined, resist emotion, hold the course. Or, if you can’t manage that, hire someone who will hold your hand through the turbulence.

Loss aversion plus recency bias, DALBAR suggests, is the worst cocktail a portfolio can drink. And millions of investors are apparently knocking them back at last call.

When the Math Doesn’t Math

There’s just one problem. Several academics have looked under DALBAR’s hood and found an engine that might be rigged.

The core issue is methodological. DALBAR compares dollar-weighted returns (what investors actually experience, given when they add or withdraw money) to time-weighted returns (the index’s performance, assuming a single lump-sum investment held throughout). These are fundamentally different measurements. A financial planner named Wade Pfau ran the numbers in a widely-cited analysis and found that even an investor with perfect timing—someone who never panicked, never chased, never made a single emotional decision—would still underperform the index in DALBAR’s framework simply because they were adding money over time rather than investing a lump sum at the start (Journal of Financial Planning, 2014).

The methodology, critics argue, structurally guarantees an appearance of underperformance. The gap isn’t measuring behavior. It’s measuring arithmetic.

This doesn’t mean behavioral errors don’t exist. They obviously do. But the magnitude of the DALBAR gap may be inflated by a factor of two or more, according to Pfau’s calculations. The study has never been peer-reviewed in academic finance journals. It’s proprietary research, sold primarily to financial advisors as a marketing tool. Which raises an uncomfortable question: who benefits from the narrative that investors can’t be trusted?

The Industry That Needs You Broken

Consider the incentive structure. The financial advisory business faces an existential threat from low-cost index funds. When the product is commoditized—when anyone can buy the entire market for nearly zero fees—the industry needs a new value proposition. And “you’re irrational and you need us” is a very good one.

DALBAR’s findings aren’t just research. They’re demand generation. Every time an advisor cites the behavior gap, they’re making the case for their own existence. The client walks in feeling capable; they leave feeling defective. The solution, conveniently, is ongoing professional management—typically for one percent of assets annually, forever.

This isn’t conspiracy. It’s economics. Financial planning, according to industry analyst Michael Kitces, has increasingly evolved from portfolio construction (commoditized) toward “behavioral coaching” (defensible). The DALBAR narrative provides the intellectual scaffolding for that pivot.

Meanwhile, the structural causes of investor underperformance get politely ignored. For most of the historical period DALBAR analyzes, low-cost index funds barely existed. Investors didn’t “choose” high-fee active funds—those were the only options. Load fees, expense ratios of 1.5% or more, and transaction costs were built into the system. Attributing that drag to “behavior” rather than “industry structure” is historical laundering.

When Panic Isn’t Panic

There’s another layer worth excavating. What DALBAR categorizes as “irrational selling” often reflects circumstances that have nothing to do with psychology.

People sell during downturns because they lose their jobs. Because medical bills arrive. Because the roof leaks and the emergency fund was always a fiction. A 2022 Federal Reserve survey found that 37% of American adults couldn’t cover an unexpected $400 expense without borrowing or selling something. For a substantial portion of the investing population, market participation is conditional on nothing going wrong. When something goes wrong, assets liquidate—not because of loss aversion, but because of loss reality.

The DALBAR framework treats all exits as cognitive failures. But for someone whose income just disappeared, selling at a 20% loss is not irrational. It’s rational adaptation to a crisis. The study cannot distinguish between “panic sold because markets felt scary” and “sold because I was about to miss rent.” It sees only the flow, not the reason.

This is worth sitting with. The dominant narrative pathologizes behavior that may be entirely reasonable given the constraints people actually face. And those constraints—precarious employment, inadequate savings, wage stagnation—aren’t personal failures. They’re structural conditions that the behavior-gap discourse conveniently overlooks.

The Privilege of Discipline

Buy and hold is excellent advice. It’s also advice that assumes a baseline of stability most households don’t possess.

To hold through a 40% drawdown, you need income that isn’t threatened by the same recession causing the drawdown. You need an emergency fund measured in months, not days. You need no high-interest debt that might become unbearable if cash flow tightens. You need, in short, to be okay—economically and psychologically—while the world briefly pretends it’s ending.

That’s not universal. According to research from the Brookings Institution, roughly half of American households could not maintain their standard of living for more than two months if their income disappeared (Brookings, 2019). For these households, market volatility isn’t noise to be endured. It’s potential catastrophe to be managed.

The DALBAR prescription—”just hold”—functions as advice for the already-comfortable. For everyone else, it’s a reproach disguised as guidance. You should have held, it says, without asking whether holding was possible.

Gamification and the Manufacture of Churn

If behavior is the problem, it’s worth asking who designed the environment where behavior occurs.

Modern brokerage platforms are not neutral interfaces. They’re attention architectures optimized for engagement. Push notifications alert users to price movements. Confetti animations celebrate trades. Infinite scroll feeds present real-time quotes like a social media timeline. According to research published in the Journal of Finance, commission-free trading and gamified interfaces increased trading frequency by 13.9% among retail investors (Barber et al., 2021).

This matters because every design choice shapes behavior. The “irrational” investor checking their portfolio six times a day isn’t acting in a vacuum. They’re responding to a platform engineered to make checking feel urgent and trading feel rewarding. The casino, in other words, is criticizing the gambler.

DALBAR measures the output of this system and attributes it to individual cognition. But cognition is downstream of design. The behavior gap may be less a bug in human psychology than a feature of an industry that profits from activity. Passive investing—the solution DALBAR’s findings seemingly endorse—generates minimal fees. Active engagement pays the bills.

The Cultural Moment

Something has shifted in how we relate to investing, and DALBAR sits uneasily within that shift.

On one side: the rise of passive indexing, the gospel of Jack Bogle, the triumph of “set it and forget it.” Vanguard now manages over $8 trillion. The message is efficiency through abdication. Stop thinking. Stop feeling. Become the market.

On the other side: meme stocks, crypto volatility, the Robinhood generation treating portfolios like identity projects. Here, investing isn’t optimization—it’s expression. The GameStop saga wasn’t primarily about returns. It was about narrative, community, and telling a particular story about yourself.

DALBAR’s findings validate the first worldview and condemn the second. But the second worldview isn’t going away. For a younger generation facing student debt, unaffordable housing, and climate anxiety, the promise of slow compound growth over forty years feels abstract to the point of irrelevance. The behavior gap, in this light, might be less a mistake than a choice—a preference for financial aliveness over financial optimization.

This doesn’t make it wise. But it does suggest the DALBAR frame misses something. Humans aren’t homo economicus optimizing lifetime consumption. They’re storytelling animals seeking meaning in how they spend their days. Sometimes that meaning looks, from outside, like irrationality.

A Different Question

What if, instead of asking “how do I fix my behavior,” we asked “what structures make good behavior difficult”?

The answer might include: platforms designed to maximize engagement, not outcomes. Fee structures that extract value invisibly. Information asymmetries where retail investors learn about opportunities after they’ve already been captured. A media ecosystem that profits from volatility narratives. An advisory industry that needs you anxious to justify its existence.

These aren’t excuses. Personal responsibility remains real. But so does system design. The DALBAR narrative locates the problem entirely within individual skulls. A more honest accounting would recognize that behavior emerges from context—and context is built by industries with interests.

What Actually Helps

Here’s what the evidence, honestly assessed, probably supports.

Behavioral errors are real but likely smaller than DALBAR suggests. The gap that remains after correcting for methodology and fees is still worth addressing—but it’s not the chasm the industry needs it to be.

Simple automation helps. Target-date funds, automatic contributions, and thoughtful default settings can eliminate most of the genuine behavior gap without expensive human intervention. According to research from Vanguard, automated features like auto-escalation increase savings rates by meaningful margins without requiring any behavioral heroics (Vanguard, 2021).

Reducing exposure to noise helps more than resisting it. Checking your portfolio less frequently isn’t willpower—it’s architecture. Delete the app. Turn off notifications. Make doing nothing easier than doing something.

And perhaps most importantly: designing your financial life around your actual constraints, rather than optimizing for an abstraction, matters more than any study suggests. If you know you’ll panic at minus-40%, a portfolio that can only fall 20% isn’t cowardice. It’s engineering for a known parameter.

The Investor in the Mirror

DALBAR isn’t wrong that people make mistakes. They do. We do. The recency bias is real. Loss aversion is measurable. The tendency to chase what just worked and flee what just failed is documented across cultures and centuries.

But the story that you are primarily sabotaging yourself—that the market is offering you riches and you keep slapping them away—is a story that serves particular interests. It justifies fees. It manufactures dependency. And it locates systemic problems in personal pathology.

Maybe the behavior gap exists. Maybe it’s smaller than advertised. Maybe it’s partially manufactured by the same industry that measures it. Maybe it’s rational adaptation to constraints that the comfortable don’t face. Maybe all of these are true simultaneously.

The useful takeaway isn’t “I’m broken.” It’s that behavior emerges from systems, and systems can be redesigned—at the platform level, the regulatory level, and the personal level. Automate what you can. Simplify ruthlessly. Build for who you actually are, not for the disciplined automaton the financial planning industry wishes you were.

And the next time someone cites the DALBAR study to explain why you need their services, feel free to ask: “Who paid for that research, and what were they selling?”

The answer might be as illuminating as any benchmark comparison.