The Portfolio That Deserves to Exist

A portfolio should be built not for the world you think is coming,

but for the set of worlds you cannot, in good faith, rule out.

That sounds vague, so let’s pin it down.

You cannot rule out:

- Inflation staying annoyingly high

- Inflation going back to 2% and never leaving

- A nasty recession

- No recession, just slow grindy growth

- A big geopolitical shock

- Or… nothing dramatic at all, just another decade of muddled status quo

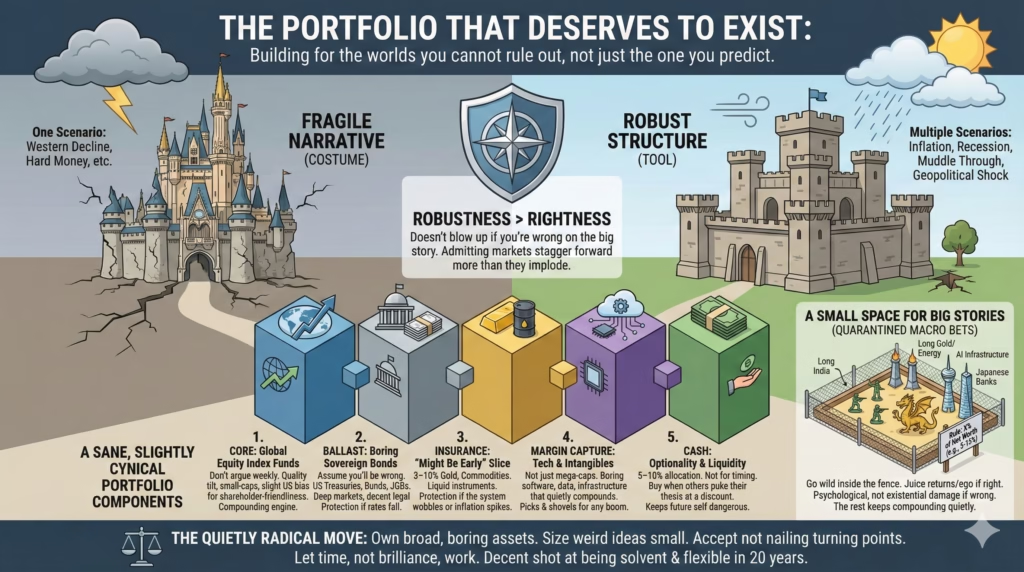

Any portfolio that only works in one of those worlds is a costume, not a tool.

The Gave-style portfolio is a costume. Beautifully tailored for one very specific movie: Western decline, Asian hegemony, hard-money renaissance, energy scarcity, and state failure in developed democracies.

That film might get made.

But what if the studio cancels it halfway through and releases something else?

What if you sit through ten years of trailers waiting for a plot twist that never shows up?

Robust > Right

There’s a boring word for what you actually want: robustness.

Not brilliance.

Not purity.

Not ideological coherence.

Just: “This thing doesn’t blow up if I’m wrong on the big story.”

Over the last 50–100 years, despite wars, oil shocks, tech bubbles, inflation spikes, and central bank experiments, a few simple facts keep reappearing:

- Global equities have delivered roughly 5–7% real returns per year over long horizons. That’s from data sets like the Credit Suisse Global Investment Returns Yearbook and work by people like Dimson, Marsh, and Staunton.

- A basic 60/40 (stocks/bonds) in the U.S. from 1980 to about 2023 delivered around 8–9% nominal annually, depending on which exact indices you pick, with far fewer catastrophic drawdowns than an all-equity portfolio.

- According to Vanguard and others who’ve run the numbers too many times, asset allocation explains most of your return variability; the sexy macro calls add noise more than signal.

You don’t need to believe in “American exceptionalism” or “the genius of the Fed” to use that information. You just have to admit that markets have a habit of staggering forward, through stupidity and drama, more often than they completely implode.

What a Sane, Slightly Cynical Portfolio Might Look Like

Think in components, not in totalizing world views.

You might have:

- A core you don’t argue with every week.

Global equity index funds. Maybe a tilt toward quality or profitability. Maybe some small-caps. Maybe a bit more U.S. than the global cap weight because, empirically, U.S. capital markets have been more shareholder-friendly than most. Nothing fancy. - A ballast that assumes you’ll be wrong about something.

Boring sovereign bonds from jurisdictions with deep markets and decent legal systems: U.S. Treasuries, Bunds, JGBs, Gilts. Duration spread out over time. The stuff everyone on podcasts calls “trash” and pensions keep buying anyway. - A slice of “I might be right, but I might be early” insurance.

Some gold or commodities. Not 70% of your net worth in Krugerrands under the stairs—more like 3–10% in liquid instruments that won’t ruin you if they underperform for a decade. Enough that if the system really does wobble, you’re not naked. - Some tech and intangible-heavy businesses that actually capture margins.

Not just the seven mega-caps; they’re fine, but crowded. There’s a long tail of boring software, data, infrastructure, and tooling names that quietly compound while everyone yells about the end of the dollar. These are the companies that will sell the picks and shovels to whatever “Ricardian” boom actually happens. - Cash.

Not because “cash is king” or because you’re timing some mythical crash. Just because optionality has value. Cash is the only asset that lets you buy when others are forced to sell. A 5–10% cash allocation is less about yield and more about keeping your future self dangerous.

The point aren’t that you must own exactly these things.

It’s that each piece should answer a very small, boring question:

- What pays me if the world just muddles along?

- What protects me if rates fall?

- What protects me if inflation spikes?

- What lets me buy when someone else is puking their thesis into the market at a 40% discount?

You end up with a portfolio that doesn’t need the world to validate your narrative on a schedule.

It won’t feel heroic; it just sort of work most of the time.

A Small Space for Big Stories

You don’t have to give up macro thinking entirely. It’s fun. It sharpens your understanding of history, politics, and how the pipes of the world actually connect.

You just quarantine it.

Make a rule with yourself:

“X% of my net worth is for big, coherent, probably-wrong theses I enjoy believing.”

Maybe X is 5%. Maybe 10%. If you’re truly deranged, 15%. But you pick a number and you fence it.

Inside that sandbox, go wild:

- Long gold and energy because you think we’re headed for hard-money renaissance

- Long Japanese banks because you believe rate normalization is finally, actually, really coming

- Long India because demographics and reform

- Long AI infrastructure because you think the Schumpeterian wave dwarfs everything else

If those work, great—you’ll juice your returns and your ego.

If they don’t, the damage is psychological, not existential.

The rest of the portfolio keeps compounding quietly in the corner, like a sturdy employee who doesn’t attend the meetings and never complains.

The Hidden Cost of Feeling Smart

A lot of what passes for “macro sophistication” right now is basically a very expensive way to avoid feeling like a sucker for owning the same stuff as everybody else.

Index funds? Treasuries? Dollar cash? That’s for the rubes.

You, on the other hand, see the matrix. You understand Eurasian landmasses and Ricardian phases and energy intensity curves.

But markets do not pay you for emotional satisfaction. They don’t care how correct your worldview feels. They care whether you were:

- Invested in things that actually made money

- In sizes you could survive emotionally and financially

- For long enough to let compounding work

According to Dalbar’s long-running studies of investor behavior, U.S. equity investors have typically underperformed the very funds they buy by 1.5–3 percentage points per year, simply because they chase narratives and bail at the wrong time. That’s not a small error; over 20–30 years it’s the difference between “comfortable” and “I hope the kids don’t move back in.”

A portfolio that constantly demands you re-affirm your worldview is a portfolio optimized to trigger exactly that behavior gap.

The Quietly Radical Move

In a world where the “contrarian” stance is elaborate macro pessimism wrapped in gold bars, the genuinely radical move is almost insulting in its simplicity:

- Own broad, boring assets that historically survive a wide range of regimes

- Size your weird ideas small enough that they can’t kill you

- Accept that you won’t nail the big turning points

- Let time, not brilliance, do more of the work

This is not spiritually satisfying.

It will not get you invited on podcasts to talk about the end of Western civilization.

But it does something rarer: it gives you a decent shot at being solvent, flexible, and only moderately bitter in 20 years.

You can still read Gave. You can still nod along when someone explains why Hong Kong will be the nexus of the new multipolar order. You can still buy a bit of gold, or a Chinese industrial, or whatever idea keeps you entertained.

Just recognize it as entertainment. As a side bet. As colour around a core, not the core itself.

The future will probably be messy, anticlimactic, and unsatisfying to every camp. No grand vindication, no clean collapse, no triumphant “I told you so” bell ringing over the ruins of the S&P 500.

In that kind of world, the smartest trade in the room is not being the smartest person in the room. It’s being the one whose portfolio doesn’t need the world to cooperate in order to work.