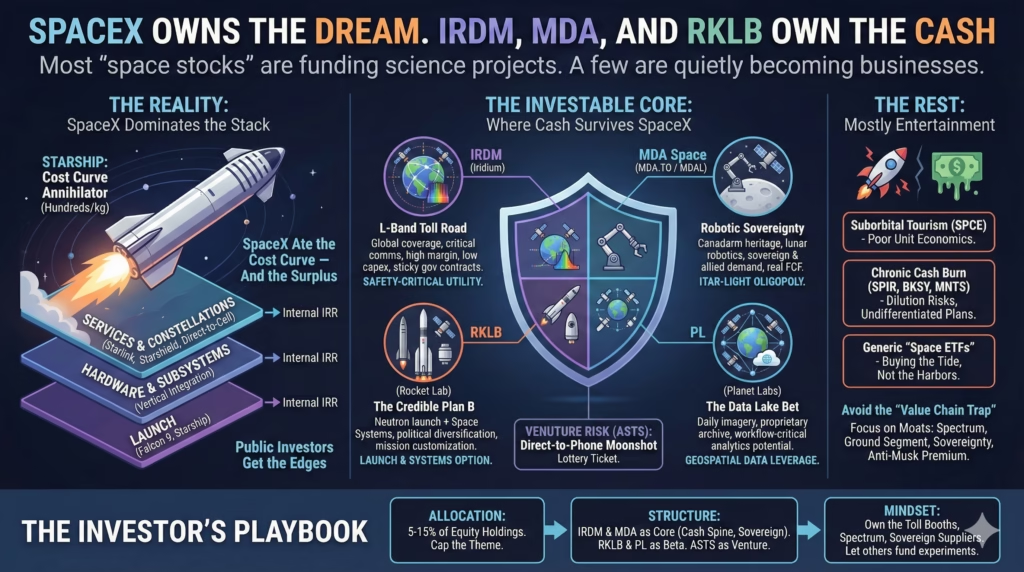

Space Stocks Won’t Make You Musk-Rich — But IRDM, MDA, and RKLB Might Actually Pay You

Most of the space economy belongs to SpaceX. The game now is figuring out what’s left over — and whether it’s worth touching.

Why This Matters Before You YOLO Into the Final Frontier

The modern space pitch sounds like a religion with better charts.

Launch costs down 97% since the Shuttle. Reusable rockets. Starship promising another 10x drop. Morgan Stanley talking about a $1.1 trillion space economy by 2040. ARK tossing around multi-trillion TAM numbers like confetti.

So the conclusion must be: buy anything with “space” in the deck, wait for the riches to arrive. Right?

Not even close.

Here’s the simple, uncomfortable frame:

- SpaceX is eating almost all the economic surplus. In 2023 it flew 96 orbital launches and handled the majority of global commercial mass to orbit; by mass and cadence it already dominates, and it’s still ramping.

- Launch is becoming a utility. When one company can reasonably aim for 140 launches in a year (per SpaceX’s own targets for 2024), pricing power belongs to the customer, not the small launcher with a nice investor deck.

- Public investors only see the scraps. The most important firm in the entire ecosystem is private and shows no urgency to IPO.

So the game isn’t “How big will space be?”

The game is: Which public names can survive in a world where SpaceX keeps winning?

Condensed into one sentence:

The right move isn’t to bet on “the space economy” — it’s to own the few durable, ugly, cash-generating corners that SpaceX either can’t be bothered with, or structurally cannot dominate.

Those corners exist:

- A boring but powerful L‑band network (IRDM)

- A sovereign robotics and satellites champion (MDA.TO / MDAL)

- A maybe-overvalued but real second-place launcher/systems house (RKLB)

- A speculative data play (PL)

- A genuine binary science project in public clothing (ASTS)

This is the tour through them, plus a few landmines to avoid entirely.

The Cult of Cheap Launch, and What Everyone Gets Wrong

The most repeated chart in space finance shows launch costs collapsing:

- Space Shuttle: often quoted around $50,000–60,000 per kg to LEO

- Falcon 9 rideshare: roughly $5,000–6,000 per kg list pricing

- Starship bulls talk about $200–1,000 per kg in a mature, reusable scenario

That’s the basis of the “trillion-dollar orbital economy” pitch.

Lower costs → more stuff in orbit → more revenue → you retiring early with a telescope and a smug grin.

There’s just one missing detail:

That cost curve is almost entirely owned by SpaceX.

According to multiple launch market analyses, SpaceX already controls on the order of 80–90% of global commercial mass-to-orbit. It not only launches its own payloads cheaply; it then uses that advantage to field its own services (Starlink, Starshield, direct-to-cell).

So when launch gets dramatically cheaper, three things happen:

- SpaceX’s constellation economics improve

- Everybody else’s pricing power collapses

- Investors in “me-too” launchers discover that lower costs don’t help when your competitor’s costs drop faster than yours

The cost curve is real.

Its investable relevance is… limited.

Cheaper launch is fantastic if owning SpaceX stock. For public markets, the real question is: Where does value accumulate that SpaceX either can’t fully crush, or isn’t allowed to own?

Follow the Money, Not the Slide Decks

Start with budgets, not dreams.

According to U.S. Department of Defense budget documents, the U.S. Space Force budget roughly doubled from about $15 billion in FY2020 to almost $30 billion requested for FY2025. By the early 2030s, a $45–55 billion annual space-defense spend is very plausible just from existing doctrinal trends.

The Space Development Agency plans hundreds of satellites for missile tracking, communications, and sensing. Those contracts are not theoretical; many are already awarded and funded.

Then layer in commercial:

- LEO broadband constellations (Starlink, OneWeb, Amazon Kuiper, Telesat Lightspeed) imply $50–80 billion in cumulative capex through 2030

- Direct-to-device (satellites talking straight to standard phones) could be a $100 billion+ addressable market if the technology and economics cooperate, according to various operator and analyst estimates

This all sounds like a gold rush. Until the demand side gets inspected properly:

- Defense is budget-constrained. The Pentagon does not suddenly buy 10x more satellites because prices fall 80%. It buys whatever force planning and Congress allow.

- Civil/commercial is only semi-elastic. Fiber, undersea cables, and 5G keep improving. Satcom is fantastic where nothing else works, but it is not replacing your urban fiber line.

The “infinite demand at lower price” narrative feels like a classic tech extrapolation grafted on a physical, regulated, political domain. Demand grows, yes. But not exponentially just because launch got cheaper.

This is where space stops looking like software and starts looking like a mash‑up of regulated utilities and defense contractors: demand nudges upward as doctrines evolve, committees debate edge cases, lawyers fight over spectrum rights, CFOs cap capex at whatever fits next to the dividend, and the PowerPoint curves that showed infinite elasticity quietly flatten into slow, policy-driven stair steps.

In other words: space is growing, but the growth is lumpy, political, and highly concentrated.

The Value Chain Trick That Suckers Public Investors

Strip the space stack into three big buckets:

- Launch

- Hardware (satellites and components)

- Services (connectivity, data, analytics)

Each looks tempting. Each has a catch.

1. Launch: a brutal commodity with a superhero incumbent

- Rocket Lab’s Electron: about $25,000/kg

- Rocket Lab’s planned Neutron: target around $3,850/kg

- Falcon 9 rideshare: ballpark $5,000–6,000/kg

- Starship bulls aim for $500/kg or less over time

Paying 8x Falcon 9’s implied Starship pricing for “schedule flexibility and mission tailoring” might work in a niche. It does not support broad, fat margins across a public company.

Launch is capital-intensive, operationally terrifying, and dominated by a private firm that treats rockets like software sprints.

That’s not a great setup for minority public shareholders.

2. Hardware: “picks and shovels” that keep getting cheaper

The common bull line: “Forget launch, own the components. Picks and shovels won the gold rush.”

Charming. Also historically overrated.

- Major constellation operators (SpaceX, Amazon Kuiper, even some governments) increasingly verticalize: they design and manufacture in-house

- Commodities like reaction wheels, star trackers, power systems, and smallsat buses face relentless price pressure

- SpaceX reportedly churns out 40+ Starlink satellites a week at production costs around $250,000 per unit for earlier batches, according to various industry estimates — and keeps driving that lower

Suppliers without deep flight heritage, proprietary know-how, or regulatory/supply-chain advantages are easily sidelined.

3. Services: attractive margins, direct line of fire

Services seem like the promised land:

- Earth observation

- Maritime and aviation connectivity

- IoT links for sensors and vehicles

- Broadband and direct-to-device

Gross margins look like software. The competition includes:

- Starlink

- Government-owned or quasi-sovereign constellations

- Established GEO satcom operators pivoting to LEO/MEO hybrids

The viable niches are:

- Sovereignty-driven demand (Europe wanting non-US options, for example)

- Classified or defense-adjacent analytics

- Very specialized, high-value data products

So the thesis shifts from “own the space economy” to:

Own the few businesses that:

- sit in structural chokepoints (spectrum, ground segment, robotics)

- have real customers paying real cash

- can survive even if SpaceX keeps execution at near-superhuman levels

The Ground Is Quietly Becoming the Real Bottleneck

Space commentary is obsessed with rockets and shiny satellites. The actual choke point is often more mundane:

Ground stations. Terminals. Antenna arrays. Spectrum coordination. The software glue that tells a thousand satellites who to talk to and when.

For LEO broadband, the inconvenient physics is this: satellites are almost a solved problem — or close enough that investors treat them that way — terminals are not.

- A typical Starlink user terminal still costs roughly $300–600 to produce and ship, depending on version and region

- Starlink has reportedly sold millions of terminals, often at or below cost initially to seed the market

- At $100–200 per terminal, the addressable mass market expands dramatically — rural households, developing markets, mobile platforms, fleets

Cheaper launch doesn’t change that bottleneck. The binding constraint isn’t “Can more satellites be lobbed up?”; it’s “Can user hardware be cheap and robust enough to make the service profitable?”

Companies (and countries) that solve:

- Ground congestion

- Smart antenna networks

- Spectrum coordination

- Secure, software-defined ground segments

…end up with something space hardware manufacturers lack: pricing power on Earth.

Sovereignty, Sanctions, and the Musk Discount

A quiet but powerful shift is underway:

Space capacity is now a sovereignty asset, not just a utility.

- European policymakers increasingly talk about “strategic autonomy” in space

- The Eutelsat–OneWeb merger had a heavy political flavor — ensuring European-friendly LEO broadband capacity even if Starlink’s policy stance diverges from EU interests

- Governments in Asia, the Middle East, and Latin America are funding or co-funding national or regional constellations purely for optionality and leverage

Walk into any European commission space briefing and the slide that gets the most quiet attention is rarely the rocket glamour shot; it’s the coverage map colored by jurisdiction and veto power, because ultimately these networks are levers in negotiations long before they are line items in P&Ls.

On top of that, there’s the Elon factor.

SpaceX/Starlink is run by a single highly polarizing figure who:

- Controls the network

- Makes policy-relevant decisions on access (see: Ukraine)

- Engages in public political commentary that unnerves some governments and corporates

That creates a “sovereignty premium” and an “anti-Musk premium”:

- Some customers will pay more for non-SpaceX options

- Some governments simply cannot rely on a US-based, Musk-controlled infrastructure for critical services

- Export-control regimes (ITAR in the US, for example) push certain work outside American borders

Enter companies like MDA Space in Canada:

Non-US, ITAR-light, with deep heritage. Suddenly the foreign address and separate legal regime are a feature, not a bug.

Iridium (IRDM): The Cash Machine Space Forgot About

Iridium is not sexy. Good. Sexy burned most of the SPAC money.

What it is:

- Operator of a global L‑band satellite constellation

- True pole-to-pole coverage

- Serving maritime, aviation, government, and IoT customers

- Think “industrial and government connectivity where nothing else reliably works”

Why it matters:

- The current constellation is fully deployed; no major replacement capex until the 2030s

- Gross margins above 90% on service revenue, according to company filings

- Spectrum rights in L-band that are globally coordinated, interference-resistant, and extremely hard to replicate

- US government as a sticky anchor customer with multi-year contracts

The rough risk-return frame often penciled out by serious analysts:

- 5-year base-case IRR: ~12–15%

- Bull case: ~20%

- Bear case: low-single-digit positive, assuming no catastrophe

- Attractive entry historically in the $28–32 region

This is not a 10x moonshot. It’s more like owning a high-margin toll road in a world that still pretends every road will be tolled by AI in the cloud.

Key things that actually matter:

- Spectrum is the hidden crown jewel.

L‑band’s interference characteristics (more robust, more reliable in bad weather and over oceans) become more valuable as higher bands crowd and jam. - The business is way past “satellite phones only.”

Maritime connectivity, aviation safety services, IoT for logistics and industrial equipment — those are boring, sticky, contract-heavy verticals. - Balance sheet strength = survival + optionality.

In a downturn, capital-starved LEO players may sell assets or spectrum rights at distressed prices. Iridium is one of the few positioned to be a buyer. - Government dependence cuts both ways.

Budget pressure hurts, but governments also pay on time and don’t churn like fickle SaaS customers. - Starship-enabled L‑band competition is the nightmare scenario.

If someone launches a rival L‑band constellation cheaply using Starship, Iridium’s moat thins. That risk feels remote, but not impossible. A smart investor prices in some chance of eventual constellation refresh and more contested spectrum.

This is the closest thing to an “anchor” in public space equities: dull, profitable, survivable.

MDA Space (MDA.TO / MDAL): The Sovereign Robotics Monopoly

MDA is what happens when a country quietly builds a space champion while everyone else is memeing rockets.

What it is:

- Canadian space technology company

- Famous for the Canadarm robotic systems on the Space Shuttle and International Space Station

- Sole provider of Canadarm3 for NASA’s Lunar Gateway

- Also builds satellite buses, radar satellites, and provides geointelligence services

Why it matters:

- A backlog north of C$3 billion in recent disclosures

- Profitable with real free cash flow

- Embedded in NASA’s lunar architecture

- Non-US, but closely allied — a sweet spot for export control and sovereignty concerns

Return profile often framed like:

- 5-year base IRR: 15–18%

- Bull case: ~25%

- Bear case: low-single-digit positive

- Historically interesting entry zone: C$14–18

What actually makes this compelling:

- Canadarm is a capability, not just a contract.

High-reliability robotics in space is a tiny club. MDA is at the center. As lunar and on-orbit servicing missions grow, MDA’s know-how is not trivial to copy. - ITAR-light manufacturing is powerful.

Some customers explicitly seek non-US origin for certain subsystems to avoid US export shackles. Canada works nicely here. - Valuation gap vs US peers.

MDA often trades at a 30–40% discount to roughly comparable US aerospace/space names, largely due to TSX listing and lower visibility. A future US listing or strategic takeout could compress that discount quickly. - Telesat Lightspeed is a single-point-of-failure risk.

A big chunk of MDA’s backlog is tied to Telesat’s LEO constellation. If Lightspeed stumbles or gets scaled back, MDA’s near-term revenue picture shrinks. - Hidden consumer exposure via Apple/Globalstar.

Apple’s Emergency SOS capability uses Globalstar satellites; MDA has been involved in satellite manufacturing there. It’s indirect, but shows how MDA quietly sits inside wider consumer narratives.

MDA is basically the “adult in the room”:

Profitable, essential, not screaming on CNBC every week.

Rocket Lab (RKLB): The Challenger Brand in a One-Player Market

Rocket Lab is the only Western name that can say “orbital launch plus meaningful space systems revenue” without blushing.

What it is:

- Operator of Electron, a small launch vehicle

- Building Neutron, a medium-lift partly reusable rocket

- Space Systems division: spacecraft buses, solar panels (SolAero), reaction wheels, and other subsystems for government and commercial constellations

In recent periods, ~2/3 of revenue has come from Space Systems, not launch. That’s… good. Launch alone is a deathmatch.

Return framing (roughly):

- 5-year base IRR: 10–18%

- Bull case: up to ~35%

- Bear case: ugly, possibly -25% or worse

- Interesting entry zone some investors eye: $4.50–5.50

What makes RKLB interesting, but dangerous:

- The Neutron faith problem.

The bull case assumes Neutron is flying commercially around 2025–2026, hits its cost targets (~$3,850/kg), and captures mega-constellation and defense payloads.

Meanwhile Starship undercuts it massively on $/kg. The argument is “schedule and mission flexibility justify paying more.” That might hold for some customers, but not for all. - Space Systems is the quiet backbone.

Components and spacecraft platforms (Photon, etc.) diversify revenue. However, expect margin pressure as more constellations insource. - Export-control optionality.

New Zealand heritage and some non-US facilities can matter in specific deals where US origin is a hassle. - Capital allocation has flashes of discipline.

Buying Virgin Orbit assets out of bankruptcy, scooping tech and hardware at cents on the dollar, is the kind of move that can compound over a decade. - Profitability is always “two years away.”

Guidance has nudged the profitability horizon from 2024 → 2025 → 2026. Realistically, assume 2027+ unless things break perfectly. Position sizing should reflect the risk that capital markets patience shrinks.

Resolution: Rocket Lab is the “credible Plan B” to SpaceX in the West. That’s worth something. But paying 18x+ revenue (where it has traded in frothier periods) for a capital-intensive business facing a super-competitor is asking for pain.

AST SpaceMobile (ASTS): Venture Capital Hiding in Your Brokerage Account

This one lives in the speculative bucket. On purpose.

What it is:

- Building a space-based cellular broadband network

- Goal: connect ordinary, unmodified 4G/5G phones directly from space

- Partners include AT&T, Verizon (trial), Vodafone, and others in various forms of MOUs and agreements

The dream: a massive, high-ARPU, wholesale-only service for mobile network operators, serving the unconnected and underconnected.

Potential:

- Addressable market estimates hover north of $100 billion if direct-to-device actually works at scale

- ASTS claims an IP moat in large phased-array antennas and network architecture

- If it works and capital is available, this could 10x. Easily.

Risks:

- SpaceX + T‑Mobile are racing on their own direct-to-cell Starlink service, with early text services already demoed and more ambitious rollouts targeted for 2024–2025

- ASTS likely needs $6–10+ billion of additional capital to fully build out its constellation, given its own past figures and industry benchmarks

- Every capital raise dilutes existing shareholders

- Technology is not yet proven at commercial scale. The BlueWalker 3 satellite showed feasibility (phone calls, data), but scaling that to a full network is an entirely different challenge

Likely outcomes:

- Many scenarios end with shareholders diluted brutally while the technology becomes… a nice acquisition for someone else

- A few scenarios end with ASTS as a key wholesale layer in global telecom

- The rest end in long, slow equity decay before a distressed takeout

Return framing:

- 5-year IRR range: anywhere from -10% to +50% on a probability-weighted basis

- Bull scenario: 10x+

- Bear scenario: -80% or worse

- Only makes sense to enter after sharp pullbacks, never as a momentum trade

This is venture capital masquerading as a public stock. Maximum position size for any rational adult: whatever can go to zero without altering life plans.

Planet Labs (PL): The “Satellite as Data Lake” Bet

Planet is the canonical example of a good idea colliding with hard economics.

What it is:

- Operator of the largest Earth observation constellation

- Daily or near-daily imaging of most of the planet at moderate resolution

- Customers: governments, agriculture, insurance, environmental monitoring, ESG use cases, and occasionally headline-grabbing imagery of wars and disasters

Financial reality:

- Revenue around the low- to mid-$200 million range annually

- Gross margins ~70%+ on a good day

- Still not profitable many years after inception

- Customer acquisition costs worryingly high; some cohorts reportedly cost more to land than they generate in near-term gross profit

The entire bull case rests on data leverage:

- The archive becomes a gold mine for AI

- Crop yield prediction

- Flood and wildfire risk modeling

- Insurance underwriting

- Supply chain and infrastructure monitoring

- Once embedded into workflows, churn falls and margins expand

- Planet becomes less “satellite operator” and more “data and analytics SaaS with unique sensors”

Return framing:

- 5-year base IRR: 5–15%

- Bull case: ~30%+ if data monetization actually hits its stride

- Bear case: -30% or worse if capital markets close and growth stalls

- Entry zones often discussed by patient investors: $2.50–3.50

Key questions that actually matter:

- Do customers truly need daily imagery, or is weekly/monthly good enough for most use cases?

- Does free or cheap government data (NASA/ESA programs) commoditize the lower end?

- Can Planet control operating costs enough to reach GAAP profitability before another dilutive raise?

The bet here isn’t on satellites. It’s on selling information and insight. If that works, margins can look software-like. If not, the hardware eventually becomes an expensive curiosity.

The Names That Belong in the Penalty Box

Some tickers in space are simple: do not touch unless in a very special situation or deep distress pricing.

Virgin Galactic (SPCE)

- Suborbital tourism with ticket prices that don’t remotely cover the cost base at meaningful scale

- Limited fleet, enormous capex, long turnaround times

- Little connection to the broader infrastructure boom

Space tourism might become a luxury niche. That doesn’t make it a good public equity.

Spire Global (SPIR), BlackSky (BKSY), Momentus (MNTS)

Different flavors of the same problem:

- Chronic cash burn

- Repeated capital raises

- Execution inconsistencies

- Business plans that effectively assume SpaceX either slows down, stops competing aggressively, or that customers are willing to systematically overpay for second-tier solutions

Could some of these pop 3x on a contract win or short squeeze? Sure.

A lottery ticket can also yield 100x. The market dont care about your TAM slides when the balance sheet is bleeding out.

For a long-term, semi-responsible portfolio, these belong in the “monitor with morbid curiosity” pile, not the core allocation.

How Much “Space” Should a Sane Portfolio Actually Hold?

Here comes the part every true believer hates.

For a typical growth-oriented investor:

- Total space exposure: probably 5–15% of total equities

- Above that, sector and single-ecosystem risk begin to dominate outcomes

- Space is still a capital-intensive, politically exposed, winner-take-most domain

Within that space sleeve, a rational internal mix might look something like:

- Iridium (IRDM): ~30% of the space sleeve

- Role: cash-generative anchor

- MDA Space (MDA.TO / MDAL): ~25%

- Role: profitable compounder with sovereignty tailwinds

- Rocket Lab (RKLB): ~20%

- Role: higher-risk optionality

- Planet Labs (PL): ~10%

- Role: data/AI upside

- AST SpaceMobile (ASTS): ~10%

- Role: moonshot, fully acknowledged as such

- Remaining 5%: cash or a broad aerospace-defense ETF like ITA for flexibility

This is not a sacred allocation. It’s a sanity check:

- Enough upside if the sector does well

- Enough ballast (IRDM, MDA) to avoid getting fully destroyed

- Clear boundaries between “businesses” and “bets”

The Few Catalysts That Actually Move the Needle

Focusing on headlines is a great way to go broke. Focusing on a small, curated list of real catalysts is better.

Positive / validation catalysts to watch:

- Starship regular operational cadence (2025–2026?)

- Cheaper secondary payloads help everyone with small sats

- Confirms the low-cost, high-mass regime is here to stay

- Rocket Lab Neutron milestones

- First flight, then credible cadence

- Real backlog announcements, not just LOIs

- MDA Telesat Lightspeed progress

- Satellite deliveries, funding clarity, ground infrastructure deals

- ASTS BlueBird satellites

- Successful launch and sustained commercial service, not just demos

- Planet Labs profitability milestone

- Any quarter with GAAP or at least consistent positive free cash flow changes the conversation

Negative / thesis-breaking events:

- Major launch failure leading to regulatory clampdowns and schedule slips across the industry

- SpaceX direct-to-cell achieving broad coverage before ASTS has enough birds in orbit

- Significant defense budget cuts (10%+ real reductions over multiple years) in the US or Europe

- Serious debris incidents accelerating Kessler-syndrome concerns and forcing tighter orbital regulation

- Endless dilution cycles at any of the discussed names, with no real operational inflection to show for it

A sector this speculative doesn’t require perfect timing, but it does require paying attention to a handful of inflection points rather than chasing every press release.

The Move From Here

Space, as an investment theme, tends to attract either sci‑fi romantics or cynical short-sellers. The truth, as usual, lives in the messy center.

Numbers is one thing; cash flow is another.

A deliberately grounded approach from here:

Decide your total “space” budget first.

- Lock a percentage of total equities (say, 10%)

- Promise not to exceed it no matter how exciting the next rocket livestream looks

Build around IRDM and MDA as the spine.

- These are not perfect, but they are real businesses with customers, margins, and backlogs

- Accumulate gradually on drawdowns; don’t chase spikes

Treat RKLB and PL as higher-beta satellite positions.

- Starter positions only

- Add if Neutron shows genuine progress or if Planet finally proves operating leverage

Handle ASTS like a venture bet, not a stock.

- Size assuming complete loss is possible

- Only add on fear, never on euphoria

- Watch BlueBird launches and partner behavior closely

Keep a foothold in diversified defense.

- Names like LMT, NOC, LHX, or an ETF like ITA, give exposure to space as a profitable line item inside diversified cash machines

- For many people, this will quietly outperform their careful hand-picked “pure-play space” basket over a decade

Be willing to be boring.

- The most lucrative move in a sector dominated by a single private giant might simply be:

- Own the defense primes

- Own one or two dull winners like IRDM

- Let everyone else fund the science experiments

Space as an industry not going away. Launch costs will likely keep dropping. Orbital capacity will keep expanding. More services will be built.

But the investable reality is cold: SpaceX captures most of the surplus.

Public investors get the edges.

The edge positions worth owning are now reasonably clear.

The hard part is resisting everything else.