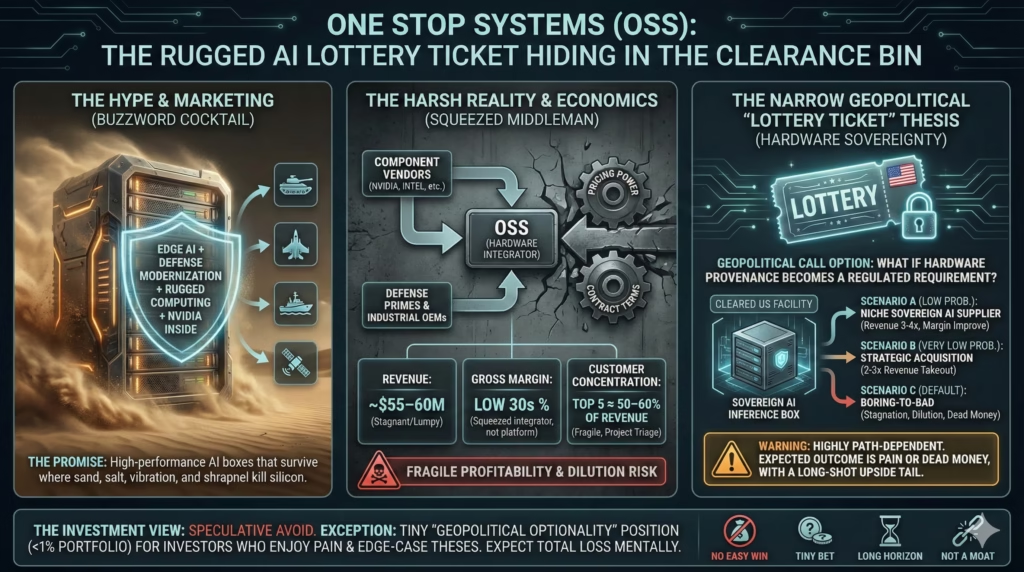

One Stop Systems (OSS): The Rugged AI Lottery Ticket Hiding In The Clearance Bin

The edge-computing war story that mostly pays its lawyers and landlords

The Fast Read For Impatient Masochists

One Stop Systems builds high-performance computers that don’t live in data centers.

They live in places that hate electronics: inside armored vehicles, next to jet engines, on oil rigs, in deserts, on ships. The company’s hardware is meant to run AI and high-end processing in all those environments where sand, salt, vibration, and shrapnel try to kill silicon.

On paper, it sounds like the perfect buzzword cocktail:

edge AI + defense modernization + rugged computing + NVIDIA inside.

In reality?

- Revenue sits around $55–60 million a year.

- Gross margins hover in the low 30s.

- Top 5 customers make up roughly half of revenue (per OSS’s own filings).

- Profitability is inconsistent at best, fragile at worst.

- Competitors 10–20x the size show up whenever a contract actually matters.

This is not Snowflake. It’s not even Supermicro. It’s a specialized box-maker fighting gravity, geopolitics, and basic economics.

Still, there is a weird, narrow, intellectually honest bull case:

a geopolitical call option.

In a world that starts caring a lot more about where AI is physically computed — which rack, which box, which facility, which country — a small, U.S.-based, defense-adjacent hardware integrator with no China baggage and cleared facilities might end up accidentally sitting in the right place.

That scenario is unlikely. Not impossible. And the stock price barely assigns it any value.

So the blunt rating:

- Core view: Speculative avoid.

- Exception: Tiny “geopolitical optionality” position for investors who enjoy pain and edge-case theses.

- Expected outcome: Mild loss or dead money, with a long-shot upside tail.

What OSS Actually Does When It’s Not Saying “AI Edge”

Strip out the marketing sugar.

One Stop Systems (ticker: OSS) is a hardware integrator. Not a chip designer. Not an AI software shop. Not a hyperscaler.

The business model is old-school:

- Buy compute components: primarily NVIDIA GPUs, high-speed interconnects, SSDs, CPUs, boards.

- Design rugged or “transportable” systems: boxes, chassis, backplanes, cooling, power.

- Certify them for brutal environments: military standards (MIL‑STD, MIL‑STD‑810, etc.), shock, vibration, temperature, EMC.

- Sell them to:

- Defense primes (Raytheon, Northrop, L3Harris, etc.)

- Industrial OEMs

- Media and entertainment (historically)

- Other niche high-performance edge use cases.

The financials line up with that role:

- Revenue: About $59 million in 2023, down from roughly $64 million in 2022 (according to OSS’s 2023 10‑K).

- Gross margin: Low 30s %, typical of a specialized integrator, not a differentiated platform.

- Operating income: Frequently negative or marginally positive. Any downturn or customer pause shows up quickly in the P&L.

- Market cap: Micro-cap territory, generally under $100 million, often far below that.

The margin profile tells the entire story, more brutally than any investor deck:

- Software businesses: 70–90% gross margins.

- Semiconductor IP: 50–70%.

- High-end branded hardware (think networking or storage leaders): 40–50%.

- Contract-like integration and metal boxes: 25–35% — where OSS lives.

In that layer of the value chain, power is almost always held by someone else:

- Upstream: NVIDIA, Intel, and the component vendors set pricing and availability.

- Downstream: Defense primes and large OEMs dictate contract terms, volumes, and schedule.

OSS, today, is a squeezed middleman with rugged niche expertise. Not a platform. Not a standard. Not systemically important.

Useful, but very replaceable.

The Mirage Moat: When “Hard To Do” Still Isn’t Hard To Copy

Management talks about thermal engineering, ruggedization, and MIL‑SPEC compliance as differentiators. And they are, in the sense that not everyone wants to bother with them.

But barriers-to-entry are not the same thing as a moat.

Consider what it actually takes to compete with OSS:

- Experience with rugged thermal management?

- Familiarity with MIL‑STD requirements and testing labs?

- Relationships with defense primes?

- Ability to qualify for government programs and handle classified work?

Now consider who already has all of that and then some:

- Mercury Systems (MRCY): Nearly $1 billion in annual revenue, deep integration into U.S. and allied defense programs, multiple secure facilities, and an R&D budget that likely exceeds OSS’s market cap.

- Curtiss‑Wright (CW): Around $2.9 billion in 2023 revenue (per company filings), entrenched in defense electronics, flight systems, and mission-critical hardware.

- A long tail of private, specialized defense electronics firms with decades of relationships and capacity.

If OSS disappeared tomorrow, customers would be annoyed for a quarter or two, then re-source the work. That is not a moat. That is a switching-cost speed bump.

Thermal design, metal bending, and running test cycles in environmental chambers are process knowledge, not deep proprietary IP. Time-consuming, yes. Not sacred.

Which leads into the next awkward truth.

When Your “Customer Base” Is Basically Five People

In OSS’s own disclosures, the top five customers represent roughly 50–60% of revenue in most years. That’s not a concentration risk. That is the entire business.

This has few obvious consequences:

- Pricing power is a fantasy.

Those customers know exactly how important they are. Any negotiation begins with: “You need this contract more than we do.” And they’re right. - Forecasts are fragile.

A single program delay, redesign, or cancellation punches a hole in the income statement. - Every project is existential.

When five logos drive most of revenue, you don’t manage a portfolio. You live by project triage.

Institutional investors hate this structure for reason. It doesn’t scale smoothly. It doesn’t compound reliably. It just sort of lurches from contract to contract.

Customer concentration also undermines the AI-marketing gloss.

If edge AI were truly exploding for OSS — in a diversified, secular way — the revenue mix would be broadening, not narrowing. New customers would show up. Legacy concentration would dilute. Instead, the opposite seems to be the default gravity.

The Defense Pivot: Camouflage Over Competitive Scar Tissue

Whenever a small tech-ish company suddenly “pivots” toward defense, it’s worth asking why.

Not the marketing why. The survival why.

OSS historically leaned into:

- Media and entertainment (on-location rendering, VFX, post-production)

- Commercial HPC (high performance computing)

- PCIe expansion and storage appliances

None of those segments are dead. They are:

- More competitive

- More commoditized

- More price-sensitive

- Less tolerant of subscale vendors

Defense has real attractions:

- Long program lifecycles once designed-in

- High switching costs after qualification

- Budgets growing in the U.S. and among NATO allies

- A political tailwind as great-power competition ramps up

Anyone who has walked the floor at a second-tier defense trade show has seen the pattern: endless rows of nearly identical black boxes, each promising “mission-ready AI” and a slightly different shade of matte paint, while the same handful of primes stroll through deciding which ones get to live for another budget cycle.

Defense is not a charity for mid-tier integrators. It is one of the most brutally negotiated ecosystems on earth. The primes — Lockheed Martin, Raytheon, Northrop, General Dynamics — squeeze their subcontractors relentlessly. Margins do not magically expand just because camouflage is involved.

Analysts love to talk about “Programs of Record” as if they’re golden tickets. They’re not.

For a company like OSS, a Program of Record usually means:

- 3–5+ years from first demo to meaningful production revenue

- Early work that can be low-margin or negative-margin just to win the slot

- Constant threat of scope changes, deferrals, or cancellation

- Volumes that often come in below the initial hero slide projections

Meanwhile, firms like Mercury Systems and Curtiss‑Wright actively hunt the same contracts, with:

- Larger engineering teams

- Broader product portfolios

- Deeper political and organizational relationships

- More flexibility to absorb loss-leader work to win strategic programs

When Mercury seriously wants a slot, smaller competitors don’t really “compete”. They just lose more slowly.

The defense pivot, in this light, looks less like strategic enlightenment and more like “get me out of commoditized media storage before the margins disappear entirely”.

Kneeling At The NVIDIA Altar

The most important supplier in OSS’s ecosystem is obvious — NVIDIA — and everything else more or less orbits that fact.

The entire AI hardware stack right now is effectively NVIDIA’s private playground. OSS does not design GPUs. It does not design the key accelerators. It buys whatever NVIDIA (and to a lesser degree others) will sell it.

That dependency bites in multiple ways:

- Pricing power runs uphill.

When NVIDIA raises prices, OSS can:

- Eat margin

- Pass costs through and risk losing on price to larger integrators who get better discounts

- Try to re-architect around cheaper silicon (rarely what defense customers prefer)

- Allocation risk during booms.

In AI booms, GPUs are constrained. Large cloud operators, hyperscalers, and tier-1 OEMs get priority allocations. Micro-cap integrators placing tens of millions of dollars in orders a year sit very far down the list. - No strategic lock-in.

OSS has no exclusive with NVIDIA. No custom silicon. No special variants. Its boxes are clever, but not irreplaceable. Another integrator with a similar bill of materials can contest any bid.

In a sense, OSS exists at the mercy of NVIDIA’s product roadmap and silicon supply, while trying to convince investors that its differentiator is…the sheet metal wrapped around those chips.

There is a business here, but it’s structurally subordinate.

The Numbers Don’t Scream “Multi-Bagger”

The 5‑year expectation has to be anchored in actual math, not just buzzword stacking.

A realistic base case over five years might look like:

- Revenue grows from ~$60M to maybe ~$80–90M with some defense wins.

- Gross margin inches up a bit if mix improves, but stays closer to low‑mid 30s than 40%.

- Operating margin stabilizes in the mid-single digits if execution is solid and dilution is not catastrophic.

- The market continues to value the firm at ~1x–1.5x revenue, which is standard for small, lumpy, low‑moat hardware integrators.

In that scenario, shareholders might see:

- 10–50% total return over five years

- Which works out to ~2–8% annualized, before considering dilution

Now factor in the almost certain share issuance:

- A subscale, cyclical, low-margin hardware company that wants to grow, bid new programs, and hold inventory for long procurement cycles almost inevitably issues stock.

- Over a 5‑year window, 20–40% dilution is a perfectly normal outcome for this kind of business.

Blend that into the picture and the realistic base expectation shrinks further.

On the downside:

- Lose one or two core customers

- Miss a couple of large defense programs

- Hit an NVIDIA allocation crunch at the wrong time

- Layer on a few poorly timed capital raises

Suddenly the 5‑year picture looks more like:

- -30% to -50% total return, more if equity issuance happens at depressed prices.

The asymmetric story on the wrong side — where risk of loss is much more probable than compounding gain — is exactly why the market doesn’t assign OSS some glamorous “AI edge” multiple.

It’s not being unfair. It’s being sober.

The Optionality That Makes This Interesting Anyway

Despite all the structural weakness, there is one genuinely intriguing angle: hardware sovereignty.

The world is fragmenting fast:

- U.S.–China tech decoupling

- Expanding export controls on chips and AI hardware

- European talk of “digital sovereignty”

- Rising scrutiny around where critical workloads run

At the same time, AI systems are moving from “fun chatbot” to “this decides what the drone targets” and “this system governs critical infrastructure”.

In that future, the question:

“Where was this AI inference physically executed, and on what hardware, under whose control?”

starts to matter a lot.

Cloud today means “scalable and convenient.”

Cloud tomorrow, for certain workloads, could mean “opaque, multi-tenant, extra-jurisdictional, politically vulnerable.”

Governments and critical operators may demand:

- Dedicated, air-gapped hardware

- Auditable hardware provenance

- Clear jurisdictional control (e.g., U.S.-only, EU-only)

- Vendors without conflicted foreign entanglements

A small, U.S.-headquartered, defense-adjacent, hardware-focused integrator with cleared facilities and minimal exposure to China suddenly looks…interesting.

Not as a trillion-dollar empire. As a niche sovereign AI hardware supplier.

One Stop Systems is not overtly branding around “sovereign AI compliance boxes,” but structurally, the company is drifting into that exact territory:

- Facilities and staff used to clearing military and government requirements

- Familiarity with audit trails, traceability, and configuration control

- Edge-focused product designs that already assume hostile, disconnected environments

- No hyperscaler conflict of interest, no need to defend a global cloud footprint

If regulations start requiring certified “sovereign inference boxes” for certain workloads — think weapons systems, critical infrastructure control, perhaps some financial systems — a vendor like OSS can become a go-to integrator for small to mid-sized programs.

This is not the central case. The probability is low. But the payoff, if it happens, is long-tailed:

- Revenue could plausibly triple or quadruple over 5–7 years in that world.

- Margins could improve modestly if the work is complex and certification-heavy.

- A takeout by a larger defense electronics firm at 2–3x revenue would not be crazy if sovereign AI hardware became a political imperative.

With a current price in the low single digits, that scenario can yield 5–7x returns — but with perhaps only 5–10% probability, and that’s before layering in the usual execution landmines, timing luck, and investor fatigue that accompany every “this time is different” defense narrative.

That is the “lottery ticket” side of OSS.

Not fantasy. Just very path-dependent.

Putting Structure Around The Chaos: A Scenario Sketch

A rough scenario matrix over 5 years might look something like this:

- Catastrophic (~20% probability)

- One or two key customers defect.

- Defense programs slip or are lost.

- Multiple equity raises at low prices.

- Investors see -70% to -90% total return.

- Bear (~35%)

- Business stagnates in the $50–60M range.

- Margins get squeezed by suppliers and customers.

- Stock grinds sideways to down, diluted by share issuance.

- Outcome: -30% to -50% total return.

- Base (~30%)

- A couple of decent defense wins.

- Revenue climbs toward ~$80M or a bit more.

- Margins improve slightly, but no substantial re-rating.

- Total return: roughly +10% to +50% over five years.

- Bull (~10%)

- Multiple meaningful Programs of Record land.

- Execution is cleaner than history suggests.

- OSS achieves mid‑to‑high 30s gross margins on a higher revenue base.

- Market slaps a modest growth multiple on it.

- Shareholders see +200% to +400%.

- Geopolitical hardware sovereignty (~5%)

- Governments and regulators demand verifiable, sovereign AI hardware for critical workloads.

- OSS leans directly into this positioning, or gets acquired as a strategic asset by a bigger player.

- Returns could reach +600% or more if this narrative catches a real bid.

Roll that all up, and the probability-weighted expected return comes out somewhere around -10% to +5% annualized.

That’s a fancy way of saying:

The most likely outcomes are boring-to-bad. The exciting ones are possible, they aren’t the default.

Who Should Touch This, And Who Definitely Shouldn’t

Start with the simple group.

Most investors should just walk away.

There easier ways to go after:

- AI exposure

- Defense exposure

- Edge-computing exposure

- Micro-cap upside

Compared to:

- A diversified small-cap growth ETF like SLYG, or

- A broad defense play like LMT, NOC, RTX, or

- A more structurally advantaged defense electronics specialist like Mercury Systems (MRCY),

OSS adds:

- Far more idiosyncratic risk

- No clear structural advantage

- Limited liquidity

- Meaningful dilution risk

The risk-adjusted profile is just not attractive for normal, sane portfolio construction.

The Trade That Might Still Make Sense (For The Right Kind Of Degenerate)

There is one narrow, defensible way OSS can fit into an intelligent portfolio.

Use it as a tiny, explicit geopolitical call option.

That means:

- Position sizing stays small.

- Think 0.25%–1% of total portfolio value, max.

- The default for most people is 0%.

- The thesis is written down clearly. Something like:

“This position is a 5-year bet that hardware provenance and sovereign AI inference become regulated requirements for critical systems, and that OSS either grows into or is bought as a key niche supplier in that ecosystem.”

- Expect total loss mentally upfront.

If that 1% goes to zero, the emotional impact should be negligible. This is not rent money. It’s the “strange edge case” slice of the portfolio. - Execution respects illiquidity.

- Use limit orders only; the average daily volume is often too thin to justify market orders.

- Spread purchases over several days if building even a small stake. Cheap micro-caps punish impatience.

- Time horizon is genuinely long.

- 3–7 years, not 6 months.

- Any thesis that depends on defense budget cycles, regulatory shifts, and geopolitics doesn’t resolve in a quarter or two.

- Exit is binary and disciplined.

- Either the geopolitical / sovereign AI angle becomes real enough that the market notices (and the stock rerates heavily),

- Or it doesn’t, and the position is culled as part of normal portfolio hygiene after a fixed horizon…

Everyone else? The correct move is probably just “no”.

For those who want defense electronics exposure without juggling micro-cap fragility:

- Mercury Systems (MRCY) has the scale, relationships, and program exposure that OSS lacks, even though Mercury has its own execution issues.

- Broad defense ETFs or large primes remain the simplest “sleep at night” options.

The Move From Here

One Stop Systems is not a hidden gem the market “doesn’t get”.

The market gets it very well:

- Subscale, low-margin integrator

- Fragile customer concentration

- Supplier dependence

- Fierce, much larger competitors

- Capital needs that likely lead to dilution

The pricing reflects that reality.

What the market probably isn’t fully pricing is the tiny chance that sovereign AI hardware becomes a real, regulated thing — and that a company like OSS is sitting in the right zip code when it happens.

So the stance:

- Rational, diversified investors: Skip it. Allocate AI and defense exposure through larger, more liquid, structurally advantaged names or ETFs, and treat OSS as outside the investable universe.

- Geopolitical and defense nerds with a taste for convex weirdness: A small, clearly-labeled, long-duration speculative position as a “hardware sovereignty call option” is logically defensible, so long as size stays tiny and the thesis is written down in advance.

- Traders chasing “AI edge” momentum: Wrong stock, wrong story, wrong time; focus on names where narrative, liquidity, and business quality actually line up.

Sometimes the smartest move with a cheap lottery ticket is still not to buy it. For a very small sliver of capital dedicated to asymmetric geopolitical bets, taking that ticket anyway — eyes open, thesis constrained, exit rules pre-defined — can be acceptable. For everyone else, the actionable recommendation is simple: admire the story, then move on to better odds.