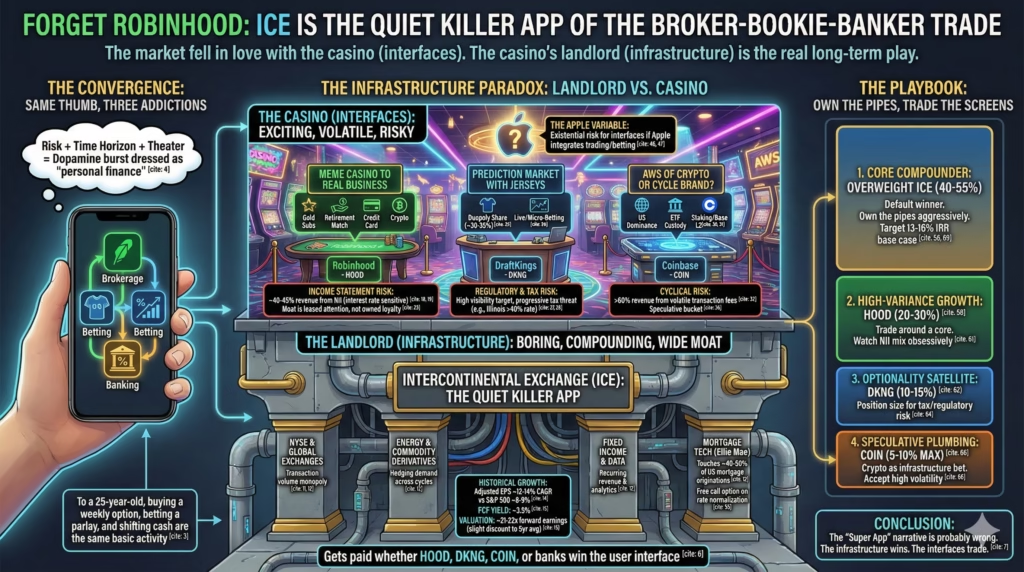

Bet the Casino’s Landlord, Not the App: Why ICE Beats Robinhood at Its Own Game

The market fell in love with the casino. The casino’s landlord is still on sale.

Why This Theme Isn’t Just Another Fintech Fad

A strange merger is happening on your phone.

The brokerage app, the sports betting app, and the bank app are slowly melting into one screen.

To a 25-year-old, buying a weekly call on NVIDIA, betting a same-game parlay on the Chiefs, and shifting cash into a 4.5% savings product are all the same basic activity:

A dopamine burst dressed up as “personal finance.”

This is the broker–bookie–banker convergence. It will reshape how money flows. That part is not controversial anymore.

The real fight is over who actually gets paid.

The market’s favorite answer is Robinhood (HOOD). The real answer is probably the opposite of that:

Boring, monopoly-style infrastructure like Intercontinental Exchange (ICE) that touches almost every transaction but never shows up on anyone’s home screen.

In rough order of attractiveness for a risk-tolerant, 5‑year growth investor, the playbook looks something like this:

- #1: ICE — Owns the plumbing for exchanges and mortgages; gets paid whether HOOD, DKNG, COIN, or Chase wins the user interface

- #2: HOOD — Real business now, not just memes; but economics lean heavily on interest rates and regulatory mercy

- #3: DKNG — Duopoly sports betting and iGaming, with tax policy as the real boss

- #4: COIN — Max upside, max faceplant potential; effectively a levered ETF on “crypto becomes infrastructure”

- #5: WBD — Cash-generative media dinosaur with good content, bad theme

The non-consensus view:

The convergence trade is real, but the “Super App” narrative is probably wrong. The infrastructure wins. The interfaces trade.

Same Thumb, Three Addictions

Scroll through a modern home screen and the boundaries of “finance” look pretty fictional.

Robinhood sits next to DraftKings.

Cash App sits next to FanDuel.

Your “high-yield savings” is just another tile next to your betting slip and your “long-term” Tesla calls expiring Friday.

According to the NY Fed’s 2024 household survey, about 40% of Americans now own stocks directly. At the same time, the American Gaming Association estimates that legal sports betting handle in the U.S. hit roughly $120 billion in 2023, up from basically zero five years earlier as states legalized it.

To someone in their mid‑20s, these aren’t different universes.

They’re sliders:

- Risk

- Time horizon

- Theater

Change the jersey and tweak the settlement rail, but under the hood it’s all probability, leverage, and payments.

The industry noticed. Everyone is trying to become everyone else:

- Robinhood is adding futures, credit cards, retirement accounts, prediction markets, and EU/UK expansion

- DraftKings is drifting closer to “financialized betting” with live, micro, and quasi-market wagers

- Banks are bolting on investing features and higher-yield wrappers to look less like utility companies

The story being sold:

All of this collapses into a single Super App.

The risk being ignored:

Users might not actually want that. And even if they do, the value may not live in the app. It may live in the pipes.

ICE: The Landlord of Risk

Intercontinental Exchange (ICE) is the unexciting answer that keeps showing up when the math is done.

ICE owns:

- The New York Stock Exchange

- Major energy and commodity derivatives exchanges

- A massive fixed-income and data business

- And, via its Ellie Mae acquisition, mortgage software that touches something like 40–50% of U.S. mortgage originations in a typical year

Every time the broker–bookie–banker convergence pushes more trading, more derivatives, more tokenized assets, more structured products — odds are some piece of that volume sneaks through ICE’s machinery.

Doesn’t matter if the trade started on Robinhood, Fidelity, Schwab, a future Apple trading widget, or a prediction app that looks like TikTok with risk.

What the numbers say:

- Over the last decade, ICE has grown adjusted EPS at roughly 12–14% per year, handily beating the S&P 500’s ~8–9% long-term earnings growth

- Free cash flow yield sits around 3.5% at current prices, with consistent double-digit FCF growth

- The stock trades at roughly 21–22x forward earnings versus a 5‑year average near 24x — a slight discount, despite an arguably better setup going forward

- U.S. mortgage originations cratered when 30-year mortgage rates blew past 7% (MBA data shows 2023 originations less than half 2021’s peak). A simple rate normalization back toward 5% could push volumes up sharply, and ICE’s mortgage tech slice could add $800M–1.2B in annual revenue over time

ICE is the classic picks-and-shovels story in a gold rush where most prospectors are also drunk.

Robinhood, DraftKings, Coinbase — these are front-end stories with high regulatory, brand, and cycle risk.

ICE sits under them all. Quietly charging rent.

Main risks:

- Antitrust heat on future M&A

- Prolonged high-rate environment further depressing mortgage activity

- Chronic mispricing because “data and exchanges” sound boring compared to meme coins and live betting

The catch is that boring monopolies tend to compound. Exciting apps tend to dilute.

Robinhood: From Meme Casino to Real Business (With a Timer on It)

Robinhood has done something impressive that the market, oddly, hasn’t fully digested.

The platform went from a 2021 meme circus hemorrhaging cash to consistent GAAP profitability. It built:

- Robinhood Gold — 2M+ subscribers paying for higher yields, margin, and perks

- Retirement accounts with a 1% contribution match

- A fast-growing credit card presence

- Crypto, futures, 24‑hour trading, and international expansion

It looks, on the surface, like the market’s favorite version of this convergence thesis.

The problem is the income statement.

According to its recent filings, roughly 40–45% of Robinhood’s revenue now comes from net interest income (NII) — basically the spread it earns on customer cash, margin loans, and securities lending while short-term rates are 5%+.

That’s not a business model. That’s a gift from the Federal Reserve.

Consensus expectations (as of late 2024) still price in 100–150 basis points of rate cuts into 2025–26. Even a moderate cutting cycle would compress that NII.

Do a napkin sketch:

- NII drops a few hundred basis points

- User balances don’t double overnight

- Funding costs don’t suddenly vanish

Reasonable estimates put the hit at $350–400M in annual revenue, which is very close to Robinhood’s current profitability. The math just doesn’t—really—leave much room for error.

The much-celebrated Gold subscription also has a nuance:

Every $1 of Gold revenue comes with heavy obligations — higher yield on cash, matches on retirement contributions, customer support, product build-out. Fully loaded, a big chunk of that “recurring revenue” is just customer acquisition cost wearing a subscription hat.

It’s clever. But clever doesn’t always equal high-margin.

The good news for HOOD:

- Clean balance sheet: roughly $6B+ in cash, no net debt

- Product velocity is genuinely strong — 24/7 trading, expansion to the UK/EU, futures and prediction markets rolling out

- Retirement accounts with matching do create some real asset stickiness; people tend not to day-trade their IRAs away on a whim

The uncomfortable piece:

Robinhood’s moat is basically attention among younger users. Attention is leased, not owned.

The same cohort that made HOOD famous also:

- Dumped Facebook for Instagram, then Instagram for TikTok

- Turned Clubhouse into a rocket ship and then into a museum

- Cycles through “this is the future” platforms every 18 months

There is some stickiness in assets, yes. But very little hard evidence that Robinhood owned the customer in any durable way. If Apple or another giant flips a switch with an equally frictionless interface and deep cash incentives, the loyalty gets tested fast.

DraftKings: Prediction Markets With Jerseys On

DraftKings (DKNG) is really just a mass-market prediction market. It wears team logos instead of ticker symbols.

The numbers are big and getting bigger:

- Legal sports betting now exists in 38 U.S. states plus D.C. (as of late 2024), up from essentially zero in 2018, after the Supreme Court struck down PASPA

- DraftKings sits at around 30–35% market share in U.S. online sports betting, more or less sharing a duopoly with Flutter’s FanDuel

- After years of setting money on fire to acquire customers, DKNG turned EBITDA positive and free cash flow positive in 2024

Once the land grab in new states slows, two things matter:

- Retention and engagement (rewards programs, live betting, parlay culture)

- Tax and regulation

On the first, DKNG is strong. Live betting and micro-betting tap into the same need that intraday options trading satisfies in markets: the illusion of control over a noisy stream of randomness, and on the second, the real risk emerges because the exact same behavioral hooks that drive engagement also make politicians and regulators extremely sensitive to optics when losses go viral or college scandals hit the news, which means any misstep can snowball quickly into hearings, headline risk, and new rules.

Illinois introduced a progressive tax on sports betting operators, with top marginal rates over 40% for the biggest players. If that template spreads, state governments can effectively cap margins permanently.

Sports betting companies can’t easily flee jurisdictions or pretend the servers are “in international waters.” They are highly locational, highly visible targets. And unlike Wall Street, they don’t have 150 years of lobbying infrastructure.

DKNG’s convergence dilemma:

- It absolutely sits on the “bookie” leg of this broker–bookie–banker triangle

- But gambling regulations wall it off from becoming a full financial super app

- And the users who treat it like a de facto prediction market on politics, macro, or events are still a small niche

Still, in a world where “serious investing” and “degenerate betting” are culturally merging, DKNG is at least playing on the right field.

Coinbase: AWS of Crypto or Luxury Brand for Cycles?

Coinbase (COIN) trades like a mirror of crypto optimism.

The bull script:

- COIN is the dominant U.S. crypto exchange and custodian

- It underpins most U.S. spot Bitcoin and Ethereum ETFs as the actual asset custodian, giving it a moat with regulators and institutions

- Products like staking, custody, subscription services, and Base (its Layer‑2 network) are supposed to de-risk revenues away from pure trading fees

- If tokenization of real-world assets (RWA) ever takes off on public blockchains, COIN becomes the on-ramp, the record-keeper, maybe even the AWS-style back end

Reality as of now:

- Over 60% of Coinbase revenue still leans on transaction fees — notoriously pro-cyclical and volatile

- Custody for ETFs is good for credibility, less good for margins; it’s a fairly commoditized service with institutional pricing power pushing down spreads

- The Base L2 ecosystem is interesting, but early, crowded, and facing massive competition from other L2s and alt chains

- The “RWA tokenization” stack is probably a 5–10+ year story, and may or may not land on public chains at all

Coinbase does have a robust balance sheet and enough cash to survive a few winters. It also has something few crypto outfits manage: some alignment with regulators and a willingness to operate in daylight.

Anyone buying COIN is, functionally, betting that:

- Crypto becomes entrenched infrastructure, not just a speculative side-show

- Coinbase keeps its institutional crown against both TradFi and offshore competitors

- Regulators don’t decide to bless a rival or force fees down to commodity levels

For most participants in this convergence theme, Robinhood’s crypto exposure is probably more than enough. COIN belongs in the speculative bucket, not the core one.

Warner Bros. Discovery: Great Content, Wrong War

Warner Bros. Discovery (WBD) looks cheap on traditional value screens:

- Trades around 6x forward EBITDA

- Generates $6–8B+ in annual free cash flow

- Owns HBO, Warner Bros. studio, DC, CNN, Max — one of the best content libraries on earth

- Carries about $39B in debt, but without an immediate refinancing cliff

If the question were, “Is WBD solvent?” the answer is yes. If the question is, “Is WBD a clean way to play broker–bookie–banker convergence?” the answer is no.

Linear TV is decaying faster than streaming is growing profitably. The strategic ping-pong between theatrical releases, streaming, and licensing makes it hard to see a simple story here.

Could there be niche upside from licensing rights into prediction markets, sports betting integration, or financialized fandom? Maybe. But that’s an optionality footnote, not a real thesis.

Anyone buying WBD is buying a deep value media turnaround, not the convergence of trading, betting, and banking.

The Infrastructure Paradox: All the Upside, None of the Excitement

The easiest mistake in themes like this is falling in love with the front-end story.

New app.

Beautiful UI.

Younger users.

Exciting CEO on podcasts.

Robinhood, DraftKings, Coinbase — these stories are fun. Screenshots look great on social media. Management teams go on CNBC.

ICE shows a chart with volumes, clearing revenues, and margin efficiencies. The CFO drones on about basis points.

Yet, look at the paradox:

- Robinhood’s apparent transformation is, to a large extent, an interest rate trade

- DraftKings’ unit economics are a legislative trade

- Coinbase is basically a macro + crypto sentiment trade

- WBD is an industry structure and debt trade

ICE is… a transaction volume and data monopoly with embedded operating leverage.

If convergence succeeds — more trading, more derivatives, more structured products, more tokenized assets, more risk packaged in clever ways — volumes rise.

Who wins most consistently from rising volumes? The landlord of the exchanges and the owner of the connectivity and mortgage rails.

If convergence fails — people keep activities siloed, regulators clamp down, or users retreat to old-school brokers and banks — stocks, bonds, mortgages, and commodity markets still exist.

Who still gets paid? The same landlord.

This is the core of the paradox.

The market is paying up for front-end “optionality” while mildly discounting the back-end that:

- Has better historical growth

- Fewer existential scenarios

- And a clearer claim on future cash flows

It isn’t risk-free. ICE has antitrust overhang and mortgage cyclicality. But the risk seems hilariously more manageable than “hope Apple forgets this space exists.”

The Human Problem: Maybe Nobody Wants a Super App

Almost everyone pitching the Super App vision talks from the supply side:

“Look at all these products that can be bundled.”

“Think about the cross-sell potential.”

“Imagine ARPU if users do everything here.”

Very few ask the simpler demand-side question:

Do people actually want one app for everything?

There’s a decent argument that average American under 40 wants segmentation, not consolidation:

- A serious place for long-term investing and retirement accounts (Vanguard, Fidelity, Schwab)

- A fun place for speculation, options, and crypto (Robinhood, tastytrade, etc.)

- A pure gambling outlet (DraftKings, FanDuel, local casinos)

- A boring bank for direct deposit, rent, utility payments (Chase, BofA, local credit unions, or even Apple/PayPal/etc.)

There’s a similar pattern in health apps: people will happily track weightlifting in one app, calories in another, and meditation in a third, even though one unified dashboard could exist; the separation helps them keep different identities and habits from bleeding into each other.

Each of these plays a different psychological role. Trying to smash them into one experience can create friction:

- The gamblers hate friction and KYC questions

- The long-term investors hate seeing flashing “Hot Options” banners near their retirement accounts

- Regulators hate anything that mixes insured deposits, margin, credit, and high-velocity gambling in one bucket

In that world, the winners are not necessarily Super Apps, but focused category killers:

- DKNG as the default for sports betting and iGaming

- One or two large brokerages (Fidelity/Schwab) for serious portfolio management

- A few front-end casinos of speculation (HOOD and its peers)

- And under it all, ICE, as the infrastructure toll collector

If that’s how things play out, the consensus “one app to rule them all” thesis dies quietly. The revenue still shows up, just in a more scattered, siloed way — and the infrastructure layer still gets its cut without having to convince anyone to download another icon.

The Apple Variable That Everyone Pretends Isn’t There

Hovering over every fintech pitch deck is a mostly unspoken threat: Apple.

Apple already controls:

- Hundreds of millions of high-income users globally

- Apple Pay, Apple Card, Apple Cash, and Apple Wallet infrastructure

- Deep bank partnerships (Goldman Sachs previously, others now circling)

- The single most valuable position in tech: the default interface on the device people stare at eight hours a day

If, at any point, Apple decides to:

- Offer commission-free stock trading in Wallet

- Bundle high-yield savings, credit, equities, and maybe basic options behind Face ID

- Offer one tap “invest spare cash into an S&P 500 ETF” as casually as loading an Apple Cash card

…Robinhood’s advantage shrinks immediately.

Apple doesn’t even need to be innovative. Just competent, integrated, and slightly generous on yield.

The same is true, though less intensely, for:

- Cash App (Block)

- PayPal/Venmo

- Traditional banks finally figuring out that their apps shouldn’t look like 2009 intranet sites

There is also regulators circling around payment for order flow, crypto, leverage, and marketing. Any of these heavyweight players can absorb the cost of regulation better than a pure-play like HOOD.

Which brings the conversation back, boringly, to ICE.

Apple doesn’t disrupt ICE. It routes through ICE.

Traditional brokers don’t disintermediate ICE. They rely on ICE.

DraftKings and prediction markets don’t erase the need for hedging in energy, interest rates, and equity indices. They may even create more of it.

Apple is a genuine existential risk for the interfaces. It’s a neutral or slightly positive tailwind for the pipes.

The Trade That Actually Makes Sense

Putting this into a portfolio instead of a tweetstorm leads to a fairly clear stance.

For someone with a 5‑year horizon and real risk tolerance, the broker–bookie–banker convergence can be expressed like this:

1. Core Compounder: Overweight ICE (roughly 40–55% of this theme)

- Treat ICE as the default winner of any convergence scenario

- Today’s multiple (low‑20s forward P/E) is not cheap in a vacuum, but cheap vs its growth, moat, and history

- Mortgage tech is effectively a free call option on rate normalization and housing turnover recovery

- Reasonable expectation: 13–16% IRR base case over 5 years if EPS keeps compounding low double digits and the multiple just holds or mean-reverts slightly

Tactically:

- Scale in on any macro panic that hits financials or anything “rate-sensitive”

- Add aggressively if mortgage headlines get too apocalyptic — that’s usually the bottom of that mini-cycle

2. High-Variance Growth: HOOD as a 20–30% Position, Not a Religion

Robinhood is the most direct “thumb dopamine” play on this convergence. It deserved its upgrade from joke to serious fintech.

But the risks are real:

- NII compression if/when the Fed eases

- Regulatory friction on payment for order flow, crypto, and marketing

- Potential Apple entry

- A user base that is loyal until the next shiny thing appears

HOOD belongs in the growth sleeve, not at the center:

- Base case might justify 15–20% IRR if execution holds and rates don’t collapse too far, too fast

- Bear case is ugly — down 15–25% or worse if NII and trading activity both weaken into a risk-off environment

Practical approach:

- Watch quarterly revenue mix obsessively — if NII isn’t being gradually diluted by other durable lines, risk is rising

- Consider trimming into big euphoric spikes on meme or crypto waves; this is the definition of a stock to trade around a core, not diamond-hand in all weather

3. Optionality on Prediction Markets: DKNG as a 10–15% Satellite

DraftKings is the cleanest public market way to express:

“Financial speculation and gambling are socially merging, and legalization hasn’t peaked yet.”

Duopoly structure, rising engagement, and early-stage iGaming tailwinds are all real.

But state tax and regulation are not academic:

- Track states copying Illinois-style progressive tax structures

- Watch for advertising and college betting crackdowns tightening further

- Stress test margins assuming another 5–10 points of effective tax bite over time

Position sizing is the answer. DKNG fits nicely as a 10–15% satellite within this theme:

- High upside if states back off the most confiscatory tax ideas

- Surviveable if tax drag is worse than expected but growth offsets some pain

4. Speculation on Crypto as Plumbing: COIN at 5–10% Max

COIN is not a must-own for this theme. It’s an amplifier.

- If crypto keeps gaining institutional legitimacy and embedding into markets, COIN can massively outperform

- If crypto stagnates or regulators box it in, COIN can easily crater 40–60% from cycle peaks

Limit COIN to 5–10% of the convergence basket at most, and mentally file it under “I accept this might go very wrong, but the call option is interesting.”

Anyone who doesn’t have strong conviction about crypto’s long-term role is usually better off riding Robinhood’s lighter crypto exposure instead.

5. Skip WBD for This Theme

WBD may succeed as a value play or a media consolidation bet. That is a separate question.

For broker–bookie–banker convergence specifically, it’s noise:

- Structural headwinds in linear TV

- Murky streaming economics

- Heavy leverage

- No clean link to trading, betting, or financial infrastructure beyond soft “content” synergies

There are easier ways to lose money.

So, Take a Side

The market wants Robinhood to be the hero of this story. The evidence quietly suggests the opposite.

- Infrastructure (ICE) has:

- Proven compounding, wide moat, low existential risk

- Clear leverage to any outcome where humans keep trading, borrowing, and gambling

- Interfaces (HOOD, DKNG, COIN) have:

- Excitement, upside, and narrative

- But also regulatory, macro, and platform risk

The stance that actually aligns with the numbers is simple, if slightly boring:

- Own the pipes aggressively

- Trade the screens opportunistically

- Size pure speculation so it can blow up without ending your plan

If broker–bookie–banker convergence becomes the defining consumer-finance story of the next decade, the landlord of the casino floor — not the flashiest game on it — is likely to walk away with most of the chips.