Space data centers: the trillion-dollar opportunity you can’t actually buy

Wall Street is selling you picks and shovels. SpaceX is building the mine.

Two banks just published breathless reports on orbital data centers. The thesis is compelling. The recommended trades aren’t.

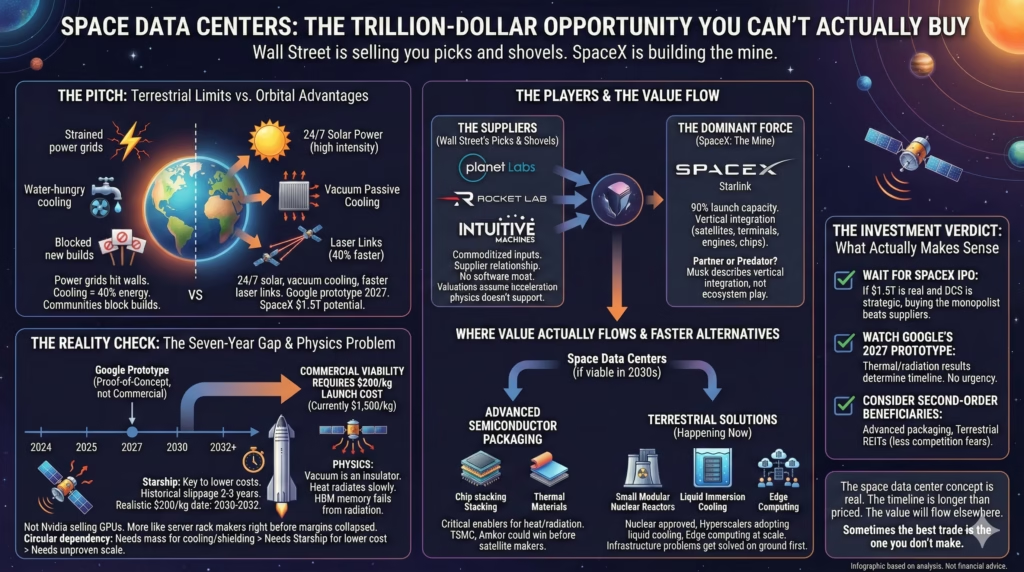

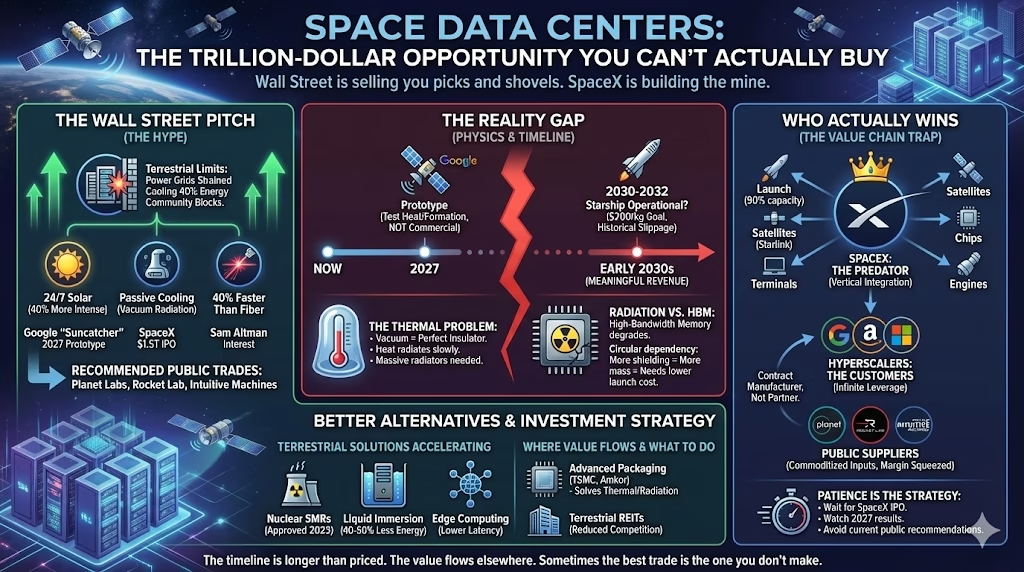

The pitch

Terrestrial data centers are hitting walls. Power grids can’t scale. Cooling consumes 40% of energy. Communities are blocking new builds.

Space offers solutions: 24/7 solar at 40% higher intensity, passive cooling via vacuum, laser links 40% faster than fiber. Google’s Project Suncatcher launches prototype satellites in 2027. SpaceX eyes a $1.5 trillion IPO. Sam Altman reportedly looked at buying a rocket company.

The math seems to work. Here’s what doesn’t: the three “well-positioned” public companies being recommended—Planet Labs, Rocket Lab, Intuitive Machines—are being set up as suppliers in a market where the dominant player builds everything in-house.

This isn’t Nvidia selling GPUs to everyone who needs AI. This is server rack manufacturers selling to AWS circa 2010, right before margins collapsed to single digits.

The seven-year gap nobody’s pricing

Google’s 2027 prototype has become the anchor date for this thesis. Analysts cite it as a near-term catalyst.

They misunderstand what “prototype” means.

The 2027 satellites will test heat dissipation and formation flying. Proof-of-concept experiments, not commercial deployments. Commercial viability requires launch costs to fall from $1,500 per kilogram to below $200—a 7-8x reduction depending entirely on Starship.

Starship has completed one successful full mission. SpaceX’s historical timeline slippage averages 2-3 years. Falcon Heavy was announced for 2013 and flew in 2018.

Apply similar slippage and $200/kg costs arrive between 2030 and 2032. Not 2027. The meaningful revenue opportunity doesn’t begin until the early 2030s—beyond any reasonable investment horizon for these names.

Rocket Lab already trades at 15x forward revenue with multiple new markets baked in. Planet Labs can’t turn a profit on its existing business. These valuations assume timeline acceleration that physics doesn’t support.

The physics problem that could kill everything

Space is cold but it’s a vacuum—a perfect insulator. Heat escapes only via radiation, which is slow.

On Earth, air flowing across a heatsink removes heat fast. In a 2-ton GPU rack, Jensen Huang notes, 1.95 tons is cooling mass. In space, equivalent cooling requires massive radiator panels adding weight, complexity, and failure points.

Google’s white paper found something worse: high-bandwidth memory began showing errors at lower radiation doses than expected. HBM is what enables large language models to function. If it degrades quickly in orbit, the entire concept faces a fundamental physics constraint.

Solutions exist—lead shielding, more thermal mass. But each kilogram makes the $200/kg threshold harder to achieve.

There’s a circular dependency nobody addresses: solving thermal and radiation problems requires adding mass, which requires lower launch costs, which requires Starship operational cadence, which requires solving challenges that remain unproven at scale.

SpaceX: partner or predator?

The sellside frames SpaceX’s dominance as a tailwind for the space ecosystem.

This fundamentally misreads how SpaceX operates.

They control 90% of global mass-to-orbit capacity. They build their own satellites, ground terminals, engines, and increasingly their own chips. When Musk says Starlink will develop modified satellites for data centers with onboard compute, he’s not describing an ecosystem play. He’s describing vertical integration.

The recommended companies occupy the exact opposite position from Nvidia. Nvidia has a near-monopoly on the scarcest resource with massive switching costs and a software moat. Planet, Rocket Lab, and Intuitive Machines provide commoditized inputs in a market where the dominant player manufactures everything in-house.

Consider Planet’s Google partnership. Planet won a “competitive process” to provide satellite buses. Google controls the payload and the high-value compute services. Planet becomes a contract manufacturer for a customer with infinite leverage who could replace them or bring manufacturing in-house at any time.

That’s not a strategic partnership. That’s a supplier relationship with a single customer holding all the cards.

Terrestrial solutions are coming faster

The bull case assumes terrestrial constraints are permanent. This conflates current problems with unsolvable ones.

Nuclear small modular reactors received NRC approval in 2023. Microsoft, Google, and Amazon have all signed nuclear power agreements. Liquid immersion cooling reduces energy consumption by 40-50% and eliminates water requirements—Microsoft deployed it at scale in 2024. Hyperscalers are building in Iceland, Scandinavia, and Canada where power is abundant and cooling is natural.

For latency-sensitive inference—the use case where space supposedly wins—the solution isn’t orbiting compute. It’s putting smaller clusters closer to users. Edge computing is already happening at massive scale.

Infrastructure problems tend to get solved on the ground before anyone figures out orbit.

The asymmetry is unfavorable. Space data centers require both the technology to work at scale AND terrestrial solutions to remain inadequate for 10+ years. If nuclear or liquid cooling advance faster than Starship, the entire thesis could be competed away before it materializes.

Where value actually flows

If space data centers eventually work, the winners probably aren’t who Wall Street recommends.

Thermal and radiation constraints both point to the same solution: advanced semiconductor packaging. Google found HBM fails faster than logic cores. Thermal limits require more efficient heat dissipation. Both point toward 3D stacking, chiplets, and advanced thermal interface materials as critical enablers.

Companies leading in advanced packaging—TSMC’s CoWoS, Amkor’s advanced substrates—could see material revenue from space-grade components before satellite manufacturers see meaningful DCS revenue.

There’s also a counterintuitive terrestrial play. If space proves viable for some workloads, the remaining terrestrial business becomes more valuable, not less. Hyperscalers shift training to space while terrestrial providers specialize in low-latency edge inference. Equinix and Digital Realty have traded down on capacity fears. If space absorbs some demand while terrestrial specializes, those fears diminish.

The valuation reality

Rocket Lab has gained 400% in 2024. At 15x forward revenue, substantial expectations are already embedded. The DCS optionality isn’t free—investors are paying for it today against revenue that won’t materialize until the 2030s, if ever.

Planet Labs trades below 4x revenue, which looks cheap until you examine the business. Persistent profitability challenges and customer concentration suggest the discount is warranted.

Intuitive Machines has interesting potential through its Lanteris acquisition, which brings satellite bus manufacturing with heat-dissipation experience. But LUNR is primarily a lunar lander company with execution risk on its core business. DCS is third-order optionality on a company that needs to prove its primary thesis first.

None of these offer compelling risk-adjusted exposure at current prices.

What actually makes sense

Wait for SpaceX’s IPO. If the $1.5 trillion valuation is real and the S-1 reveals DCS as a strategic priority, SpaceX itself is the cleanest play. They control launch, manufacturing, and will likely control compute. Buying the monopolist beats buying its suppliers.

Watch Google’s 2027 prototype results before committing capital. If thermal and radiation issues prove tractable, timelines accelerate. If they prove worse, the thesis delays by years. No urgency to position ahead of knowable information.

Consider second-order beneficiaries. Advanced packaging companies could see demand before satellite manufacturers see revenue. Terrestrial REITs could benefit from reduced competitive intensity. These aren’t obvious space plays, which means the optionality may be mispriced.

For the three public names being recommended, the current risk/reward doesn’t justify positions. Better entry points will emerge. They always do.

The space data center concept is real. The timeline is longer than anyone’s pricing. And the value, when it arrives, will flow to places other than where Wall Street is pointing.

Sometimes the best trade is the one you don’t make.