Buying the Drone Revolution with AVAV and Friends: Great Story, Terrible Timing

When everyone chases flying robots, the real money still clings to the plumbing

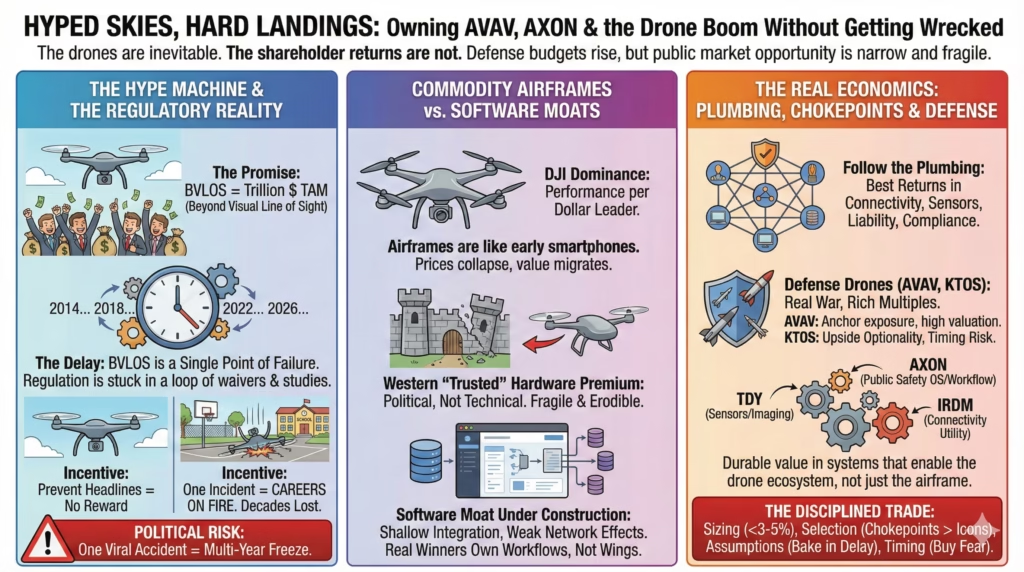

Why This Drone Dream Needs a Cold Shower

Drones in dangerous places feels like a done deal. Put machines where humans get killed, lower insurance, better data, higher margins. Defense budgets are inflating. Chinese hardware is getting squeezed out of government use. Regulators keep hinting that “this is the year” for Beyond Visual Line of Sight (BVLOS).

And yet — a decade into this supposed secular boom — most listed drone names are still lighting cash on fire, issuing shares, and pointing at regulatory PowerPoints instead of income statements.

The core mistake: assuming “drones are inevitable” means “drone stocks must be buys.” Technology adoption and shareholder returns often have a messy, distant relationship. Think of how much value the internet created versus how much the average late-1990s dot-com investor actually kept.

Most of the investable space is split between:

- Expensive defense names like AeroVironment (AVAV) that already price in a lot of good news

- Risky, small-cap or micro-cap stories dependent on regulation that refuses to show up on schedule

The opportunity is narrower, more fragile, and more sideways than the marketing decks suggest. There is a way to participate — by sizing small, being patient, and favoring chokepoints and infrastructure over shiny airframes.

The uncomfortable position: the drone theme is real. The public equity opportunity is much smaller than the narrative, and probably belongs in the “spice rack” of a portfolio, not the main course.

Perpetual Sunrise: BVLOS and the Rule That Never Lands

The entire bullish drone script leans on one phrase: BVLOS — Beyond Visual Line of Sight.

No BVLOS, no real scaling. One operator staring at one drone at a time is not a revolution. It’s a hobby.

So the story always goes like this:

“BVLOS rules are coming soon. Once the FAA finalizes the framework, commercial drone use will explode. Utilities, logistics, public safety, you name it.”

That story has been re-run since roughly 2014.

- 2014: FAA Pathfinder program promises BVLOS progress around 2016

- 2016: Part 107 arrives; waivers are supposed to be the ramp to scale

- 2018: UAS Integration Pilot Program is announced as the “real” catalyst

- 2020: Remote ID is pitched as the final puzzle piece

- 2022–2024: BVLOS ARC recommendations, NPRM “soon”, final rule “2026-ish”

A decade of “almost”.

This isn’t incompetence. It’s incentives.

The FAA exists to keep airplanes from falling on people. Not to help venture-backed drone startups hit their Series D revenue targets.

Inside the agency, the risk-reward math looks roughly like this:

- Approve aggressive BVLOS rules and nothing bad happens → no bonus, no credit, industry gets the upside

- Approve aggressive BVLOS rules and one serious incident hits the news → congressional hearings, public outrage, career damage, pain

The institution does exactly what its incentive structure tells it to:

Study. Pilot. Waiver. Delay. Repeat.

Many bullish models assign maybe a 30–40% chance to BVLOS slipping beyond 2027. That’s optimistic. Based on the last ten years of behavior and the political risk of one ugly accident, a 60–70% probability of meaningful delay is more realistic.

The data is messy, and some of it doesn’t quite line up, but the pattern is clear: nothing in FAA history suggests fast, clean rulemaking around novel risks in shared airspace.

One Bad Afternoon from a 5–7 Year Reset

Run a simple scenario.

It’s June 2026. A commercial drone operating under a BVLOS waiver suffers a failure over a U.S. suburb. It falls into an elementary school playground. Three kids injured. One goes to ICU.

The incident rate for small drones today is low, but not zero — and that “not zero” is what keeps regulators up at night. As flight hours expand, incident probability compounds, and over a five-year window with tens of millions of flight hours this sort of event is not some far-out tail, more like a one-in-three style risk than one-in-a-hundred, with each additional waiver, pilot program, and “limited deployment” quietly nudging those odds higher.

Now replay the political sequence:

- 72 hours: wall-to-wall media coverage, video on social feeds, “killer drone” headlines

- 1 week: members of Congress demanding answers from FAA leadership

- 1 month: hearings scheduled, BVLOS waivers suspended “pending review”

- 3–6 months: emergency local bans, aggressive state-level restrictions, dozens of lawsuits

- 1–2 years: NTSB reports, new safety requirements, additional testing mandates

BVLOS rulemaking doesn’t just slip a year. It gets shoved into the next political cycle. Realistic delay: 5–7 years.

Every listed “commercial drone adoption” play gets taken to the woodshed.

Down 50–80% is very feasible because these are narrative-driven stocks with low current cash flows and high expectations.

Any portfolio built on “BVLOS is basically a lock by 2027” quietly short a nasty regulatory headline.

Propellers, Meet Commoditization

Even if BVLOS landed cleanly tomorrow, a more basic problem would show up: hardware is already a commodity in most segments that matter.

Check the market structure:

- Most estimates put DJI at roughly 70–80% market share for small drones globally (consumer and a big chunk of enterprise), despite U.S. government restrictions on Chinese gear in sensitive use

- Competing Western vendors are:

- More expensive

- Often less capable

- Riding on “trust” and “sovereignty” branding, not technical superiority

The bullish pitch usually goes like this:

“Sure, DJI dominates now, but for safety-critical and government applications, reliability and trust will justify paying up for U.S. or allied vendors. That’s the moat.”

One problem:

DJI drones have flown billions of cumulative flight hours with extremely low failure rates in the field. Whatever else one thinks of Beijing, the flight logs don’t care.

The premium for “non-Chinese, Blue-UAS compliant, high-trust hardware” is political, not strictly technical. Political moats tend to be:

- Leaky (exceptions, waivers, “dual sourcing”)

- Time-limited (rules get softened when budgets bite)

- Highly sensitive to the next administration or budget crisis

Now add the smartphone analogy:

- Early iPhone era: differentiation mattered, margins were lush

- Android era: hardware became “good enough”, prices and margins collapsed for everyone but Apple

- Today: dozens of functionally similar handsets, only a few ecosystems capture durable value

The small-drone world sits closer to the late stage of that curve. Many airframes are “good enough.” Cost, not subtle performance edge, start to dominate.

That alone should give most public investors pause when looking at richly priced airframe-heavy stories.

The Software Moat That Hasn’t Been Dug Yet

There’s a popular escape hatch:

“Hardware will commoditize, but software and data will have real moats. The winners will be workflow owners, not propeller-makers.”

Conceptually correct. Practically premature.

At this stage, drone software and data platforms are:

- Fragmented across vendors and verticals

- Light on switching costs (export data, retrain a few staff, move on)

- Thin on network effects (no dominant marketplace or must-have platform)

Even Axon (AXON) — arguably the closest thing to an “operating system” for law enforcement — is very early in drones. The installed moat for tasers and body cams is very real; the drone side is still basically a bolt-on.

A few things are missing before one gets true software defensibility:

- Standardized workflows across agencies and industries

- Deep integration into back-end systems (evidence management, asset management, claims, etc.)

- Regulatory dependence on specific reporting/data formats that entrench incumbents

Right now, software in drones mostly behaves like software in an early PC clone era: lots of small players, no single gravity well.

That will change — slowly, then all at once when some dull-sounding standard finally locks in. But betting on public names as if that phase has already arrived is several innings early.

Defense Drones: Real War, Stretched Valuations

Defense is the part of the drone story that is undeniably real.

Ukraine and other modern conflicts showed:

- Small drones can be decisive at the tactical level

- Loitering munitions are rewriting artillery and infantry dynamics

- Cheap, attritable systems can punch far above their unit cost

This validates the technology. It does not automatically validate current stock prices.

Take AeroVironment (AVAV):

- Deeply integrated in U.S. and allied procurement

- Switchblade loitering munition is a known brand post-Ukraine

- Multi-year backlog, strong positioning in small tactical UAS

All positives. Now look at the other side:

- Valuation in 2024 frequently hovered around 30–40x forward earnings and 5–7x revenue — roughly 2x typical defense primes on most metrics

- The market is already assuming:

- Sustained conflict or restocking

- Continued leadership in loitering munitions

- Successful execution without major competitive disruption

AVAV isn’t some hidden gem. It’s a good business, priced like a very good business, in a sector where political cycles and procurement surprises happen.

Kratos (KTOS) sits further along the risk spectrum:

- Exposure to “Loyal Wingman” style jet drones and target drones

- Some counter-UAS capability, which is underrated

- Big upside if the Air Force and others really lean into its platforms

But also:

- Huge contract timing risk

- Attractive ideas living in PowerPoint for longer than investors stay solvent

- Valuation that already bakes in meaningful success in programs not fully locked down

Then comes the structural problem:

Small-cap defense contractors tend to do one of two things over time:

- Get acquired by primes at modest premiums (20–40%), limiting upside

- Get outgunned by primes when a critical category goes mainstream

The most interesting new defense-autonomy firms — Skydio, Anduril, Shield AI — remain private. Their owners understand the value accrual curve and have no rush to open the capital-structure kimono to public markets.

Public investors are mostly getting the names that couldn’t raise another big private round on favourable terms. That’s negative selection, not a conspiracy, just how capital markets work.

The TAM Slide That Should Be a Crime Scene

Every thematic drone deck has The Slide.

“Total Addressable Market (TAM), 2030: $XX billion.”

Public safety. Infrastructure. Logistics. Agriculture. Magic.

Anyone who has sat through a corporate “innovation day” has seen a cousin of it: a breathless market number, a rainbow of segments, and no one volunteering to explain who exactly signs the purchase order.

Start with public safety, because it’s the cleanest place to show the math drift.

- Around 18,000 law enforcement agencies in the U.S.

- Optimistic assumption: 50% have meaningful drone programs by 2030

- Reality check: surveys and field data suggest adoption is rising, but many programs are tiny, and budgets are tight. Something like 20–30% with material spend seems more honest.

- Optimistic annual drone spend: $50k–100k per agency

- Reality check: most programs are a couple of drones, training, software; closer to $15k–30k for the median agency is more likely

Now do the math.

Bullish spreadsheet world:

50% of 18,000 = 9,000 agencies

9,000 × $50k–100k = $450m–900m annual TAM in the U.S. alone

Reality-based world:

25% of 18,000 = 4,500 agencies

4,500 × $15k–30k = $67.5m–135m annual TAM

That’s a 7x–10x haircut immediately. And this is before considering:

- Free or low-cost federal programs

- Agencies sharing equipment across jurisdictions

- Hardware reuse over longer cycles than vendors pretend

Infrastructure inspection has similar issues.

Bull pitches often compare drones to helicopter inspections, claim 80–90% savings, then extrapolate across every powerline on Earth.

Reality:

- A lot of inspection today is done by trucks and crews, not helicopters

- Many assets can be monitored by fixed sensors or cameras

- Drones introduce their own costs: pilots, planning, data processing, liability, reporting

In many real-world cases, drone inspection is more expensive than truck-based patrols, particularly at small scale or in complex terrain. Worth it sometimes, but not automatically cheaper.

TAM slides take the one use-case where drones shine economically, then silently apply that margin uplift to everything that has a physical footprint. The spreadsheet doesn’t even sweat as it lies.

Where the Real Money Quietly Hides

The mental shift that de-hypes this whole thing:

Drones are not “products.” They’re nodes in a system.

At scale, the limiting factor isn’t the airframe. It’s:

- Connectivity & spectrum – how thousands of flights talk to the ground

- Airspace management – who prevents mid-air collisions between drones and manned aircraft

- Edge compute – who processes video and sensor data on the device or nearby

- Liability & insurance – who takes the legal and financial hit when something goes wrong

- Compliance & audit trails – who produces the data regulators and courts will accept

Some likely winners, none of them pure “drone companies”:

- Iridium Communications (IRDM)

- Already provides global satcom coverage

- BVLOS in remote or non-cellular regions basically needs this sort of link

- Iridium Certus is being positioned for unmanned and industrial IoT use

- If remote autonomous systems (not just drones) scale, Iridium gets recurring revenue

- Semiconductor and edge compute vendors (example: Lattice Semiconductor, though not in the earlier list)

- Low-power FPGAs and specialized chips end up inside the drone or its immediate infrastructure

- Every step toward onboard AI inference creates incremental demand

- Data and risk model owners (example: Verisk in insurance)

- If drones become a standard tool in claims, inspections, underwriting, new risk models and data feeds get priced into every policy

- The value sits in who defines acceptable risk, not who takes the photo

- Counter-drone (C-UAS) players

- Airports, stadiums, prisons, energy facilities — all have more to fear from hostile drones than to gain from friendly ones

- Government agencies are often faster to write checks for mitigation than for innovation

- C-UAS budgets respond to perceived threat, which rarely goes back to zero

Also quietly brewing: Unmanned Traffic Management (UTM) and certification capture.

Whoever builds the de facto operating system for low-altitude unmanned traffic — or writes the safety standard others must comply with — gets a moat that looks more like Visa than like a drone OEM.

- Skydio is deeply involved in FAA working groups, especially on autonomy and safety cases

- If one autonomy stack becomes the “gold standard” for BVLOS approvals, everyone else ends up proving “equivalence” or licensing it

- Blue UAS–style programs can turn into cartels of pre-cleared vendors, with high pricing power inside the walls

The catch: most of these obvious leverage points are inside private companies or buried within sprawling conglomerates.

The public “drone pure-plays” are mostly the least interesting part of the stack.

Dissecting the Listed Names Without Falling in Love

A pragmatic ranking of the better-known tickers from the earlier outline, with risk-adjusted reality injected.

AeroVironment (AVAV) — Defense First, Hype Second

- Core business: small tactical UAS and loitering munitions for U.S. and allies

- Strengths:

- Deep DoD relationships

- Proven systems in real conflicts

- Healthy backlog and solid engineering culture

- Weaknesses:

- Valuation rich relative to peers

- Highly exposed to defense budget and conflict cycles

- Limited commercial footprint

Base case: mid-single to low-teens annual return if everything goes reasonably well and valuation slowly normalizes.

Bull case: conflict and restocking last longer, new programs hit, returns drift toward high-teens-plus.

Bear case: peace dividend plus competition compress margins and multiples → negative returns even if revenue grows.

Axon Enterprise (AXON) — The Workflow Giant That Might Absorb Drones

- Core business: tasers, body cams, evidence management cloud

- Real moat: decades of contracts, embedded software, high switching costs

- Drone angle:

- Axon Air integrates drones into the same workflow as cameras and evidence

- Strong potential to own the liability and policy wrapper around police drone use

Right now, drones are a rounding error in Axon’s P&L. The stock is more a bet on continued 20–25% growth in its core business at a premium multiple.

As a “drone play,” Axon is like buying Amazon back in the day for its book sales. Wrong framing. Great company, mislabelled thesis.

Teledyne Technologies (TDY) — FLIR as a Footnote

- Owns FLIR, the go-to thermal sensor brand for many drones

- Broader portfolio in sensors, imaging, and instrumentation

- Drone-related revenue likely <5% of total

Teledyne is a quality industrial/scientific conglomerate with strong capital discipline and cash generation. If it fits a portfolio, it should be owned for that reason. The drone exposure is real but small, more of a bonus than a driver.

Buying TDY as a “drone stock” is like buying a major oil company for its electric vehicle charging pilot program.

Kratos Defense (KTOS) — Optionality With a Migraine

- Target drones and experimental jet drones (like Valkyrie)

- Some counter-UAS capability

- Aligned with future concepts like “loyal wingman” and attritable assets

Upside if:

- Loyal wingman programs scale fast

- Kratos keeps a central role

- Counter-UAS demand accelerates and Kratos wins share

Downside:

- Prime contractors push them to the margins

- Big programs get delayed or downsized

- Valuation compresses on missed expectations

Position size here should be small, treated like a call option embedded in equity form.

Iridium Communications (IRDM) — The Quiet Recurring Revenue Play

- Global LEO satellite constellation focused on narrowband services

- Already used for aviation, maritime, remote IoT

- Perfectly placed for:

- Remote BVLOS operations

- Other unmanned and industrial systems far from cell towers

Starlink and other players add competitive pressure, but Iridium’s niche — robust, low-bandwidth, safety-focused links — is more defensible than it looks at first glance.

If drones, autonomous vehicles, and remote industrial systems all scale, Iridium wins slowly and steadily, one subscription at a time. Not flashy. Potentially durable.

A Portfolio That Respects Gravity

Putting numbers on this theme is where most investors go off the rails.

For a reasonably diversified, growth-tilted equity portfolio, drones and related plays belong in something like the 0–5% of liquid net worth bracket. More than that and the tail risks (regulation, politics, accidents, hype cycles) start to matter too much.

One example of a sane sizing for someone who wants exposure but also wants to sleep:

- AVAV: 1.5–2%

- Role: defense-flavored anchor, direct drone exposure

- AXON: 1–1.5%

- Role: workflow and liability play; drones as “future option” on top of core franchise

- KTOS: 0.5–1%

- Role: speculative upside on autonomous combat and counter-UAS

- IRDM: 1%

- Role: connectivity infrastructure that benefits from many autonomy trends, not just drones

- TDY (optional): up to 0.5%

- Role: quality industrial with minor drone upside

Call it 3–5% total, with AVAV and AXON doing most of the work, and KTOS as the wild card.

Everything else in the portfolio stays boring on purpose: broad global indexes, quality compounders, some cash, maybe a few other uncorrelated themes.

The important part is not hitting the “perfect” allocation. It’s recognizing this:

- The drone theme is earlier-stage than the headlines suggest

- The public equity expression of that theme is thinner and more fragile still

- Upside is capped by already-elevated valuations in the few real winners

- Downside is amplified by binary regulatory and political risk

Treat drones as a niche, not a core allocation, and the game suddenly looks much more rational.

The Move That Actually Respects Risk

Boil down the noise, and a few concrete actions stand out.

1. Cap the Theme Before It Caps You

- Hard rule: drones + adjacent names (AVAV, AXON, KTOS, IRDM, TDY, etc.) stay under 5% of the total portfolio

- Inside that, multiple small positions beat one giant “all-in AVAV” bet

- Revisit position sizes whenever:

- BVLOS headlines hit

- Major accidents or political blowups occur

- Defense budgets shift sharply

2. Favor Systems and Chokepoints Over Shiny Airframes

When choosing between:

- A company selling complete drones into a crowded field

- A company selling something required by multiple drone makers (connectivity, sensors, workflows, insurance, traffic management)

… lean toward the second category.

That usually means:

- Names like AXON and IRDM get priority

- Airframe-heavy small caps with weak balance sheets get deprioritized, regardless of their glossy investor decks

3. Assume BVLOS Takes Longer Than Anyone Admits

Investment decisions should be robust to:

- BVLOS slipping into the early 2030s

- Patchy, waiver-driven operations continuing as the norm

- Occasional high-profile incidents resetting the clock

If a thesis only works with “BVLOS by 2027 and smooth scaling thereafter,” it’s not a thesis, just hope dressed up.

4. Watch Counter-Drone and Insurance Like a Hawk

The fastest-growing revenue lines in this ecosystem may not be “more drones,” but:

- Stopping drones (C-UAS systems, sensors, software)

- Insuring drones (liability wrappers, specialty coverage, data-backed risk models)

Most pure plays here remain private or buried in larger defense/insurance names. But any time a listed firm shows:

- Real contracts in C-UAS

- Repeatable insurance partnerships or risk-as-a-service products

…it deserves a closer look.

5. Be Ready to Buy Panic, Not Headlines

The most attractive entry points are unlikely to come on glowing BVLOS news. They’re more likely to arrive:

- After a nasty incident and a 30–50% drawdown in the whole complex

- After a “peace dividend” scare hits defense names

- After a failed hype cycle where investors get bored and move on

Drones are not going away. The world has already seen what they can do on battlefields, in disasters, and in infrastructure. Public equity returns will be lumpy, political, occasionally ugly.

The sensible stance now:

- Stay structurally underweight the dream

- Own a few of the better-positioned names at disciplined size

- Treat regulatory progress as a bonus, not a base case

- Park the bulk of capital in sturdier, less glamorous businesses that compound without needing a single FAA rule to land on time

In portfolio terms, drones should be seasoning, not the stew.