The Canadian Dividend Trap

How “safe” income quietly kneecaps your future

There’s a certain smug warmth that comes from owning Royal Bank.

You know the drill.

Quarterly deposits hit your account like rent from a tenant who never complains.

The share price doesn’t move like some deranged tech stock.

Your dad owned it. Your grandfather probably did too.

You picture your kids someday “living off the dividends.”

It feels like common sense.

Grown‑up investing.

No hype, no drama, no crypto bros.

The comfort is real, math ain’t. And the gap between the two is where a lot of Canadian retirement dreams quietly goes to die.

Why the seduction works so well

You’re not crazy for liking Canadian dividend stocks. The system was built to make you like them.

We have a tidy little cartel economy:

- Banks in a protected oligopoly

- Pipelines strung across irreplaceable corridors

- Utilities with regulated returns

- Telecoms that carved up the country like it was cold pizza

Fortis has lifted its dividend for 50+ straight years. Canadian Utilities for 52. That kind of consistency looks holy in a world where apps go from unicorn to bankruptcy between product updates.

Then Ottawa sweetens the deal.

In a taxable (non‑registered) account, eligible Canadian dividends get the dividend tax credit. Because the company already paid corporate tax, you get a break on personal tax. For middle‑income investors, that break is huge.

According to CRA tables, someone in Ontario earning about $40,000 in eligible Canadian dividends can face an effective tax rate in the single digits. Meanwhile, $40,000 in interest income? Taxed like regular employment income.

Now compare that to U.S. dividends:

- 15% U.S. withholding tax off the top

- Then Canadian tax on what’s left

- Total drag often north of 30–35%

So on paper, it’s simple:

Canadian dividends = warm, tax‑efficient hug

U.S. stocks = foreign annoyance, tax form clutter

Then comes the really intoxicating bit: yield‑on‑cost.

You buy Royal Bank at $80. It pays you $4 per share. That’s 5%.

Fast forward twenty years and—assuming the business just muddles through—the dividend has tripled to, say, $12.

You run the math: $12 / $80 = 15% yield‑on‑cost.

Fifteen percent “income.” From a blue‑chip. Tax‑favoured.

The story basically writes itself:

“Why gamble on U.S. tech stocks when I can collect 15% on my original cost from a 150‑year‑old bank?”

Because that’s not actually what’s happening.

The uncomfortable math no one wants to look at

While Canada was perfecting the art of paying 4–6% dividends, the rest of the world was busy compounding wealth.

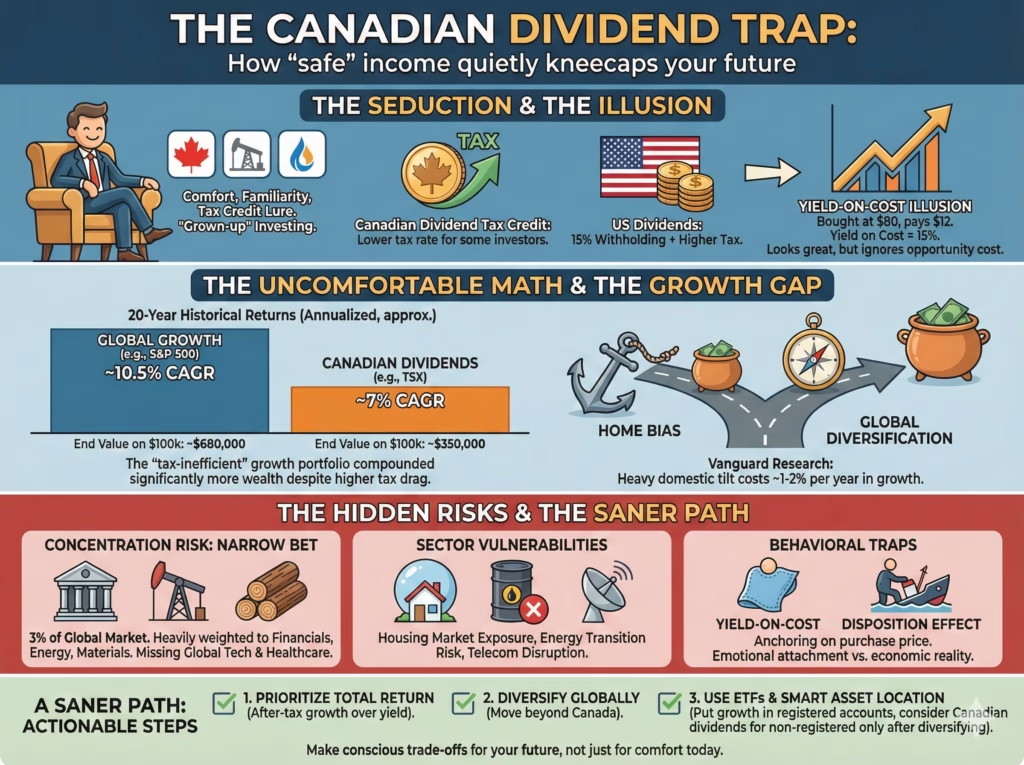

According to S&P Global data, over the last 20 years:

- S&P 500 (U.S.): roughly 10.5% annualized return

- S&P/TSX Composite (Canada): roughly 7% annualized

Three and a half percentage points doesn’t sound deadly. Until you compound it.

Let’s do the kind of scenario that dividend bloggers love, but with honest numbers.

Scenario A: Classic Canadian dividend portfolio

- Invest: $100,000

- Return: 7% per year (TSX‑ish)

- Dividend yield: 4%

- Effective tax on dividends in a non‑registered account: ~7%

- Time: 20 years

End value: around $350,000 (after taxes on dividends along the way, assuming reinvestment).

Scenario B: Boring U.S. index investor

- Invest: $100,000

- Return: 10.5% per year (S&P 500‑ish)

- Dividend yield: ~1.5%

- Assume ~35% total tax drag on those dividends (withholding + Canada)

- Capital gains taxed only at the end, 50% inclusion

End value: roughly $680,000.

Nearly double.

That “tax‑inefficient” U.S. portfolio, despite higher tax on distributions, still leaves you with dramatically more money.

This isn’t some cherry‑picked five‑year AI bubble. It’s two decades of actual market history.

According to Vanguard’s own research on home bias (2023), Canadian investors who tilt heavily toward domestic equities lose an estimated 1–2% per year in missed diversification and growth. That doesn’t show up on a statement. It just shows up as “less life later.”

The dividend tax credit you’re worshipping is mostly compensating you for giving up access to the main engine of global wealth creation.

Yield‑on‑cost: the investor’s security blanket

Yield‑on‑cost is fantastic… as a psychological trick.

Economically, it tells you almost nothing useful.

If Royal Bank trades at $140 today and pays a $5.60 dividend, the world does not care that you bought at $80:

- Your actual yield is 4% ($5.60 / $140)

- Your actual asset is a $140 security you could sell today

- Your real question is: “Is a 4% yield on a Canadian bank, at today’s valuation and risk, better than what I could get elsewhere?”

Yield‑on‑cost ducks that question and gives you a warmer one: “Am I clever for having bought this years ago?”

Imagine an investor with:

- $200,000 total contribution over decades into Canadian dividend names

- Market value today: $500,000

- Annual dividends: $25,000

They brag, correctly: “My yield‑on‑cost is 12.5%.”

But their current yield is 5% ($25K on $500K).

If that same $500K, in a global equity portfolio, could plausibly compound at 2–3 percentage points more per year over the next 20 years, the brag is expensive. Over two decades, a 2.5% gap turns $500K into:

- At 7%: about $1.9 million

- At 9.5%: about $3.1 million

That 12.5% yield‑on‑cost “victory” might be a $1.2 million shortfall.

Behavioural economists have seen this movie before.

The Journal of Finance has documented the disposition effect: investors cling to losers (won’t sell below cost) and sell winners too soon, because they anchor on their purchase price instead of current value and opportunity cost.

Yield‑on‑cost is just the disposition effect in a suit and tie. It turns your emotional attachment into a metric.

The stability myth Canadians love telling themselves

The dividend story leans hard on one main claim:

“These companies are rock‑solid. They’ve paid through everything.”

The banks survived the Depression. The Great Financial Crisis. COVID.

Pipelines hum along, shipping hydrocarbons no matter who’s in Ottawa.

Utilities keep the lights on. Telecoms send the bills.

It all feels permanent.

A few cracks:

1. Survivorship bias is doing a lot of work

We remember Royal Bank’s 150‑year streak. We don’t remember:

- The trust company crisis in the 1980s

- Canadian Commercial Bank and Northland Bank failing in 1985

- The long grind of forced mergers and rescues that left us with the Big Five

The winners look inevitable only because everyone who didn’t make it went silent.

2. Protection is nice… until you want growth

Canadian banks are protected from serious foreign competition. Good for margins. Bad for innovation.

Expanding into the U.S.? Retail banking there is brutally competitive.

Pipelines? New projects face regulatory, environmental, and political walls on all sides.

Telecoms? Ottawa is actively leaning on them about prices, and regulators like the CRTC have discovered they enjoy being on the evening news.

The moat that defends you from competition also often defends you from growth.

3. Sector risk is not magically cancelled by dividends

Three quick realities:

Banks

Canadian banks are sitting on roughly $2 trillion in residential mortgage exposure in a housing market that is, by most global measures, still wildly expensive.

The Bank of Canada’s 2024 Financial System Review notes that household debt‑to‑income ratios remain near record highs. A large chunk of bank balance sheets is a levered call option on Canadian real estate not imploding.

Pipelines

Enbridge and TC Energy own incredibly valuable infrastructure—for a world that consumes a lot of fossil fuels.

The International Energy Agency’s Net Zero scenario calls for oil demand to drop about 75% by 2050. You don’t need to believe that exact number. You just need to admit that “eternal growth in hydrocarbons” isn’t a sure thing. Pipeline assets can become stranded. Cash cows can become… former cows.

Telecoms

Bell, Rogers, Telus: a cosy oligopoly, once.

Now:

- Starlink beams internet into rural Canada from space

- The federal government uses “cell phone bills are too high” as an evergreen talking point

- The CRTC increasingly experiments with forced wholesale access, price pressure, and rule‑making that doesn’t care much about your dividend

“Stable dividend payer” can quietly morph into “politically convenient punching bag.”

The “they’ve always paid” argument sounds a lot like “Kodak has always dominated film” did in 1995.

The collector’s trap

One of the sneakiest things about dividend investing is how it turns your biases into hobbies.

Dividend investors love to:

- “Know their companies”

- Build positions over years

- Track dividend histories

- Celebrate increases like birthdays

All of this feels like discipline. A craft, even.

Oddly, it’s not that different from people who collect vinyl records or fountain pens; half the pleasure lives in the tracking, comparing, cataloguing, not in the actual sound or handwriting.

On a psychological level, it also maps neatly to:

Endowment effect

We overvalue what we already own, just because we own it. Experiment after experiment shows people demand far more money to give up something than they’d ever pay to get it in the first place.

Confirmation bias

If you love Canadian banks, you will read every bullish report. Bearish ones are “overblown.” Regulatory warnings are “politics.” U.S. banks in trouble? “See, ours are better.”

Overconfidence

Research cited in the Quarterly Journal of Economics shows frequent traders underperform by as much as 7% per year versus the market because they’re sure they know better. You might not trade often, but if you’re hand‑picking fifteen Canadian names while ignoring the rest of the planet, the mindset isn’t far off.

ETFs, boring and faceless as they are, don’t suffer from any of this:

- They sell winners when they get too big

- They add to unloved sectors automatically

- They have no idea what Royal’s slogan is

- They don’t remember what they “paid”

They just follow rules. Which is usually better than following your feelings.

The big bet nobody admits they’re making

Let’s zoom out.

Canada is about 3% of global stock market capitalization.

Sit with that for a second: three cents of every invested dollar on earth is here, in our banks and pipelines and miners and a smattering of tech, and yet most Canadian DIY portfolios you see on message boards are 60, 70, 80% home‑country names because it feels safer, because the tickers are familiar, because the news flow is in your own currency and language and you can picture the head office lobby.

A portfolio that is 70–90% Canadian dividend stocks is not conservative. It’s a huge concentrated bet on:

- One country

- A few sectors

- A particular political and regulatory regime

The TSX is heavily tilted to:

- Financials: ~30%

- Energy: ~18%

- Materials (resources): significant chunk

- Technology: ~10%, and that’s mostly Shopify and Constellation Software, which barely pay dividends

Healthcare—the largest driver of S&P 500 growth in many periods—barely exists on the TSX.

So the actual “safe high‑dividend” bet you’re making is that:

- Resource extraction stays structurally profitable

- Canadian housing doesn’t suffer a true generational repricing

- Bank regulation remains permanently friendly

- Energy transition is slow enough that pipelines keep gushing cash for decades

- And somehow Canada participates meaningfully in AI, biotech, quantum, and everything else without really having those sectors today

Meanwhile, the World Bank data shows Canada running persistent current account deficits for most of the last decade. Productivity growth has trailed peers. A depressing amount of national energy is stuck in bidding wars for detached homes built in 1972.

Again, not a political rant. Just pointing out: “all‑in on Canadian dividend payers” isn’t low‑risk. It’s narrow‑risk disguised as comfort.

Diversification is not about owning fifty tickers that feel different. It’s about not having your net worth held hostage by one set of government policies and one set of sectors.

The dividend tax credit: nice, but notice the fine print

Let’s revisit the part of the story Canadians love the most:

“But the tax treatment, though.”

Yes: the dividend tax credit is real, and in a taxable account it can slash your marginal tax rate on eligible Canadian dividends down to very friendly levels.

Zoom out one more notch.

Governments only hand out tax credits for behaviours they want to bribe you into doing:

- Film credits: “Please shoot your movie in our province, not the next one.”

- Oil & gas incentives: “Please keep drilling here while we figure out what ‘transition’ means.”

- Ag subsidies: “Please don’t abandon this region completely.”

The dividend tax credit says, in effect:

“Without a special incentive, rational money might prefer to go build chips, software, or biotech in other countries. Please keep it here in our banks and utilities instead.”

It’s not generosity. It’s economic policy.

If you optimize for “maximum dividend tax credit,” you’re solving the wrong problem. The goal isn’t:

Minimize tax per dollar of income this year.

It’s:

Maximize after‑tax wealth over your lifetime.

A smaller slice of a much larger pie beats a tax‑efficient nibble off a stale one.

What actually matters (and what doesn’t)

This is not an argument that:

- Dividends are bad

- Canadian companies are trash

- You must only buy U.S. tech ETFs or you’re stupid

Royal Bank is well‑run. Fortis and Canadian Utilities do important, unglamorous work reliably. Enbridge will almost certainly still be around ten years from now.

The problem is the framework, not the ticker symbols.

It’s a framework that:

- Treats tax efficiency as the finish line

Saving tax is not the game. Ending up with the most usable money is the game. Those two lines cross, but they’re not the same line. - Confuses yield‑on‑cost with actual return

The only thing that matters is what your dollars can earn today, from this point forward. The past is not compounding. - Mistakes familiarity for insight

Knowing a CEO quote from the annual report doesn’t give you an edge over the global market. It just gives you a sense of comfort. - Systematically ignores opportunity cost

Every dollar in a Canadian pipeline is a dollar not in global healthcare, software, semis, small caps, or emerging markets. That trade‑off is invisible, but extremely real. - Redefines “safety” as “low drama”

Real risk isn’t seeing prices move. It’s waking up at 72 and realizing your “stable” portfolio quietly lagged the world by a few percent a year for decades.

So what does a saner path look like?

No magic here. Just less Canada‑centric fantasy.

- Start with global diversification

Canada is 3% of the global market. Your portfolio doesn’t need to be 3%, but it also doesn’t need to be 83%. - Use total‑return thinking

Stop asking “What’s the yield?” and start asking “What’s the after‑tax total return I might reasonably expect from this?” Dividends are one way money comes back to you, not the only way. - Let ETFs do the boring work

Own low‑cost global or all‑world equity ETFs as your core. If you really like playing dividend collector on the side, fine—do it with a defined slice, not the whole pie. - Put the right stuff in the right accounts

In a TFSA or RRSP, the dividend tax credit does nothing. Zero. Canadian dividend stocks are not special inside registered accounts; the tax advantage lives only in non‑registered. So: - Fill registered accounts with global growthy stuff you don’t want taxed

- If you must hold Canadian dividend names, tilt those to non‑registered—after you’ve diversified globally

- Re‑define “income” as a habit, not a feature

You don’t need a stock to spit cash to create income. You can sell 3–4% of a portfolio each year just as easily as you can clip a dividend. The market doesn’t care which line the money comes from.

The real reason this is hard to change

The Canadian dividend cult doesn’t survive on spreadsheets. It survives on story.

It tells you:

- You’re prudent, not greedy

- You’re patient, not impulsive

- You’re smart enough to ignore fads

- You’re doing what responsible adults do with money

That’s a very flattering story. Way more flattering than:

“I own some boring global index funds and rebalance once a year.”

Moving away from all‑in Canadian dividends often means:

- Selling names you’ve held for 10, 20, 30 years

- Triggering capital gains tax

- Admitting, in a quiet way, that maybe the last decade of “strategy” was mostly emotional comfort wrapped in spreadsheets

Most people won’t do that. And that’s okay. Nobody is obligated to run their life like a hedge fund.

Some genuinely prefer:

- Lower expected wealth

- Higher psychological comfort

That’s a rational trade‑off if you make it, consciously.

What’s not great is drifting into that trade‑off because your advisor liked bank stocks, your parents did fine with utilities, and the dividend tax credit looked clever on a brochure.

The more honest question isn’t:

“How much income is my portfolio generating?”

It’s:

“Given where the world is going—not where it’s been—am I giving my future self the best shot at having options?”

If it helps, nobody really knows what they’re doing with this stuff anyway, we’re all just picking the mistakes we can live with. The Canadian dividend trap is just one of the more comfortable ones.