What Really Happens If Your Canadian Broker Blows Up

There’s a small, awful thought that shows up right after you transfer a big chunk of money into a new brokerage account.

It doesn’t arrive during the welcome email or the slick marketing video.

It shows up a week later, usually late at night, when your brain is bored and mean:

“If Questrade disappears tomorrow… do I actually get my money back?”

In Canada, the official answer is soothing:

- Your assets are segregated.

- They’re legally yours.

- There’s insurance.

- Sleep well.

Reality is a bit different: the system is both very good and more fragile than the sales brochures let on.

If you understand that tension, you’ll make better choices than 95% of investors who just assume “CIPF = magic shield” and move on.

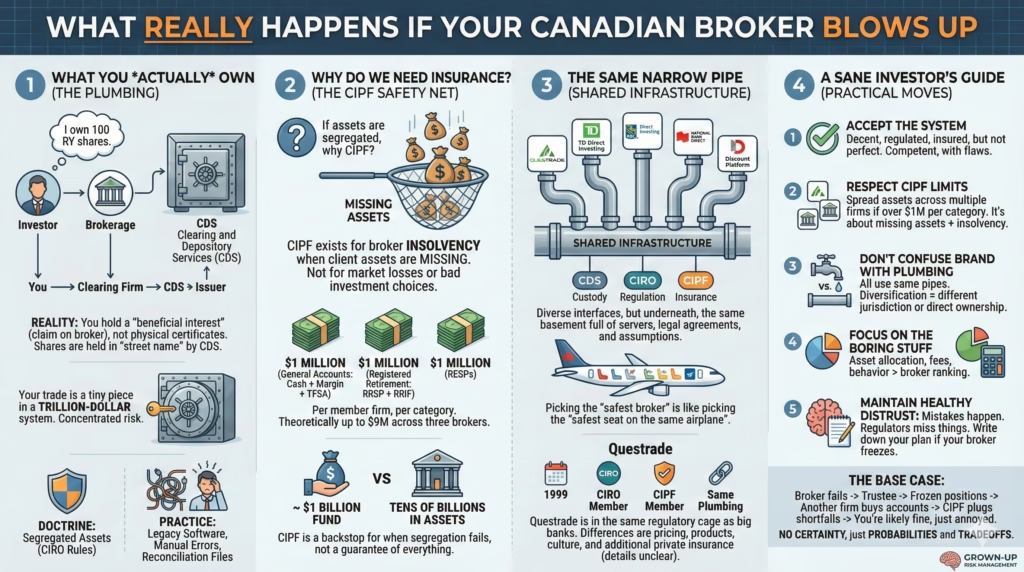

What You Actually Own (Hint: It’s Not Shares in a Drawer)

Say you buy 100 shares of Royal Bank in your Questrade account.

The story in your head: I own 100 RY shares. Questrade just keeps them for me.

The story in the plumbing:

- Your broker records that you have a beneficial interest in 100 shares.

- Those shares are held in “street name” by CDS Clearing and Depository Services (CDS), the central securities depository.

- There’s a chain: you → Questrade → their clearing firm → CDS → issuer.

You don’t hold share certificates. You hold a claim on a broker, who holds a claim on another financial institution, which holds a claim inside a giant electronic vault.

According to CDS, it handles almost all equity and fixed-income trades in Canada and settles transactions with a total value in the trillions of dollars every month. That’s efficient, standardized, systemically very convenient. Somewhere in that flood of settlement messages is your tiny trade, indistinguishable from pension funds and hedge funds and high-frequency shops; it’s a bit like dropping your house key onto a key ring that also happens to open half the buildings in the city.

It’s also concentrated. If any single point in that chain has a problem—operational, legal, cyber, “Bob wiped the wrong server”—your perfect, abstract ownership becomes a very real, very boring paperwork problem.

On paper, client assets must be segregated. CIRO (the Canadian Investment Regulatory Organization) requires dealers to keep your securities separate from the firm’s own property. In a bankruptcy, customer assets shouldn’t be used to pay creditors.

That’s the doctrine.

The practice involves:

- legacy software,

- reconciliation files,

- people typing things on tired Fridays.

The paperwork alone are a risk.

If Everything’s Segregated, Why Do We Need Insurance?

Here’s the puzzle that cracks the whole thing open:

If your assets are truly separate, untouchable, and perfectly tracked…

why does Canada need the Canadian Investor Protection Fund (CIPF) at all?

CIPF exists for a very specific moment:

when a broker becomes insolvent and cannot return all client assets it is supposed to be holding.

Not:

- your stocks going down,

- you buying junk,

- your meme options expiring worthless.

CIPF steps in only when the system itself can’t hand you back what the records say you own.

The coverage limits, as of today, is:

- $1 million for general accounts combined (cash + margin + TFSAs + FHSAs, etc.)

- $1 million for registered retirement accounts combined (RRSPs and RRIFs)

- $1 million for RESPs

Per member firm, per category. Spread your $3 million just right, and you can theoretically get $9 million in coverage across three separate brokers. Or you can not do that and just hope.

According to its recent annual reports, CIPF manages a fund on the order of $1 billion, with additional standby lines of credit. That sounds like a lot—until you remember that a single decent-sized broker can have tens of billions in client assets.

The point isn’t that CIPF is useless. It’s that its role quietly admits something:

Segregation doesn’t always work perfectly in real life.

In an insolvency, you can easily get:

- missing or inconsistent records

- unclear custody chains

- assets stuck at sub-custodians in other countries

- legal disputes over whose name something is really in

- a court-appointed trustee trying to untangle it all while everyone’s angry

Insurance is there to plug the gaps between theory and practice.

It’s not there to guarantee your returns. It barely even guarantees your stuff.

It guarantees that if your stuff is missing in the wreckage, there’s a pot of money to rebuild enough of it.

That’s a very different promise than “don’t worry, we’ve got you.”

It All Goes Through The Same Narrow Pipe

Whether you use:

- Questrade

- TD Direct Investing

- RBC Direct Investing

- National Bank Direct

- or that discount platform a YouTube guy swore was “the future”

…all of them run through the same basic infrastructure.

- Trades clear through a handful of big clearing firms.

- Securities custody ends up at CDS.

- Dealers are overseen by the same national regulator, CIRO.

- Insolvencies go into the same insurance pool, CIPF.

The surface looks diverse: different apps, interfaces, commissions, minimum account sizes, customer service horror stories.

Underneath, it’s basically a shared basement full of servers, legal agreements, and assumptions.

This has upsides:

- massively lower transaction costs

- standardized settlement

- predictable regulation

It also means that “picking the safest broker” is often like “picking the safest seat on the same airplane.”

Some seats are noisier. Some bumpier. The wings look comforting until you remember where the fuel is.

If CDS ever had a serious operational or cyber event, or one of the giant clearers got into trouble at the wrong moment, everyone would be improvising together.

You don’t reduce that risk by switching from TD to Questrade or back again. You just change call centre hold music.

Okay, But What Does Questrade Actually Bring?

Questrade is not a basement operation.

- It’s been around since 1999.

- It’s a CIRO member.

- It’s a CIPF member.

- It uses the same custody and settlement plumbing as the bank-owned firms.

Functionally, that puts it inside the same regulatory cage as the big-bank brokerages.

The differences are mostly:

- pricing structure

- product availability

- brand and culture

- what they choose to say “no” to

Questrade has also said it carries additional private insurance beyond CIPF. That’s not unusual. Several Canadian firms do this. But the details—insurer, coverage limits, exclusions—aren’t fully public.

So should you assume it’s a massive extra safety net?

No—at least, not without seeing the fine print.

Should you assume it’s worthless?

Also no.

It’s like a second fire extinguisher in a building. Helpful in some scenarios; irrelevant in most; not a magical shield against arson, earthquakes, and your neighbor microwaving tinfoil.

The Quiet Battle Over What You’re Allowed To Buy

Here’s one real, practical difference between bank-owned brokerages and independents like Questrade: what they let you touch.

The banks have periodically blocked or restricted things like:

- high-interest savings ETFs that compete with their own deposits

- leveraged and inverse ETFs

- some crypto-related products

- funds from rival asset managers

They call it investor protection.

Skeptics call it margin preservation.

According to the Ontario Securities Commission, product shelves and conflicts of interest are a live concern in Canada: banks earn fees from in-house products, and that can shape what clients see or don’t see.

For a reasonably self-aware investor, this gets annoying fast.

- You read about a covered-call ETF? Your bank says no.

- You want a particular US-listed ETF? Your platform says “not approved for retail.”

- You want to park cash in a non-bank high-interest ETF? Funny, that ticker doesn’t exist in the search bar.

Independent brokers generally have broader shelves and fewer “sorry, not for you” dialogs. That’s good if you understand what you’re buying.

It’s bad if you’re just chasing yield, volatility, or vibes.

Freedom cuts both ways. You get:

- fairer access to certain tools

- a better chance to blow yourself up without anyone stopping you

The “Sovereignty” Story That Sells Well but Doesn’t Exist

There’s a fashionable storyline online:

- Bank brokers = “captivity,” “legacy system,” “clueless advisor in a suit.”

- Independent brokers = “financial sovereignty,” “taking control,” “you and the markets, no middlemen.”

Nice idea. Wrong continent.

Switching from, say, RBC Direct to Questrade changes several things:

- your costs

- your platform

- your lineup of available products

- who sends you passive-aggressive secure messages

What it doesn’t change:

- that your securities live in an indirect holding system

- that everything settles through CDS

- that you’re relying on CIRO’s rulebook

- that insolvency risk is backstopped by CIPF

- that a web of custodians and sub-custodians stand between you and the actual shares

Real sovereignty in capital markets would look more like:

- direct registration of securities with a transfer agent in your own name

- owning assets that are physically in your possession

- or transacting on systems where you hold the keys and there is no custodial counterparty

All of those come with:

- clunkier processes

- higher friction

- new kinds of risk (loss, theft, no recourse, operational headaches)

For most investors, that’s not attractive, and that’s fine. But it’s worth being honest: moving to an independent broker gives you more latitude inside the same system, not escape from it.

You sort of get use to the cage if the food is good and the bars are polished.

The Canadian System’s Awkward Strength: It’s Never Really Been Hit

Canadian finance likes to dine out on 2008.

No big bank failures.

No Lehman moment.

No televised scenes of people lining up outside their broker to get their cash.

The Bank of Canada’s regular Financial System Review still describes the system as “resilient”, while also fretting (in polite central bank language) about:

- high household debt (over 180% of disposable income, according to Statistics Canada)

- elevated home prices

- global financial shocks that don’t check passports

CIPF has paid out in the past—there have been small dealer failures. Those cases were manageable; the fund did what it was supposed to do.

What has never happened yet:

- a major national discount broker collapsing during a period of market stress

- a serious data corruption or cyber event hitting client position records

- multiple CIPF members going under close together

- a failure that eats meaningfully into the fund’s capital

So the system’s track record is… paradoxical.

Its success is real.

That same success means some of the ugliest scenarios exist only in simulations, memos, and vague risk models.

Models don’t panic. Investors do.

So What Does a Sane Investor Actually Do?

A few practical moves, stripped of drama:

1. Accept that Canada’s setup is… pretty decent.

Relative to a lot of countries, you have:

- regulated dealers

- enforced segregation rules

- a functioning clearinghouse

- actual investor insurance

It’s not perfect. It’s not a scam. It’s a competent, bureaucratic machine with ordinary flaws.

2. Respect the CIPF limits.

If you’re bumping up against the $1M / $1M / $1M categories at a single firm, don’t be lazy.

- Spread assets across multiple member firms if you want more protection.

- Remember: that protection is against insolvency + missing assets, not markets.

Is it a hassle to manage two or three platforms? Yes. Welcome to wealth.

3. Don’t confuse brand with plumbing.

A big blue logo on your debit card doesn’t mean your brokerage arm operates on magic rails.

An online broker with no branches doesn’t mean your assets live in a sketchy offshore database.

Underneath, same pipes, same regulators, same depository.

Every so often, someone will spend an entire evening debating whether Questrade’s interface feels “cheap” compared to a bank’s or whether the shade of green in one app is more reassuring than another, and you can almost see their future returns leaking out of the room while they argue about fonts and login animations instead of contribution rates, tax planning, or the boring question of what they’d do if their account was suddenly frozen for six weeks.

Real diversification of infrastructure would mean:

- a second brokerage in another jurisdiction

- or some assets in direct form: registered shares, physical gold, that sort of thing

Not everyone needs that. Some do.

4. Keep your eye on the boring stuff.

Your asset mix, fees, savings rate, tax efficiency, and behavior in a downturn will matter orders of magnitude more than which Canadian broker custodies your VEQT.

Most people should spend 10x more time on their asset allocation than on micro-ranking broker safety.

5. Maintain a small, healthy distrust.

Not paranoia. Just a standing assumption that:

- mistakes happen

- regulators miss things

- risk models are fine until the day they’re not

- narratives—“banks bad,” “independent good,” “Canada safe”—are always incomplete

Write down what you believe about your own risk tolerance and what you’d actually do if your main broker froze for a month. That exercise is more valuable than memorizing every footnote in the CIPF brochure.

Where This All Lands

If Questrade, or any major Canadian broker, went under tomorrow—well, odds are:

- a trustee would step in

- your positions would be frozen for a while

- another firm would likely buy the accounts

- CIPF would plug any genuine shortfall up to its limits

- you’d mostly be fine, just annoyed and slightly older

That’s the base case. Not guaranteed. Just where the evidence and incentives point.

The Canadian investor protection system is real, not imaginary. It’s also partial, human, and untested at the outer edges.

You don’t get certainty. You get probabilities, tradeoffs, and the option to think just a bit harder than the average person clicking “I agree” on the account opening docs.

Your broker will almost certainly never blow up.

If it does, you’ll probably get most or all of what you’re owed.

The gap between “almost certainly” and “probably” is where grown-up risk management lives. The rest is just interface design.